Walt Whitman is easily one of America’s most well-known poets. His collection, Leaves of Grass, was published in eight editions during his life, each with revisions and an expanded set of poems that celebrated American democracy, individualism, and life, and connected individuals to each other and to nature with a “barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.” Whitman was deeply intertwined with the art world during his life, and after several years of backlash for his unconventional style, his poetry became a major influence for artists.

Prior to the publication of the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, Whitman was a huge and public supporter of the arts. His friendship with fellow poet William Cullen Bryant, one of the figures in Asher B. Durand’s Kindred Spirits, introduced him to a number of Hudson River School artists and artists of the American Art Union, and Whitman passionately involved himself in New York’s growing arts scene during the mid-1800s as an advocate for the important impact of art on democracy.

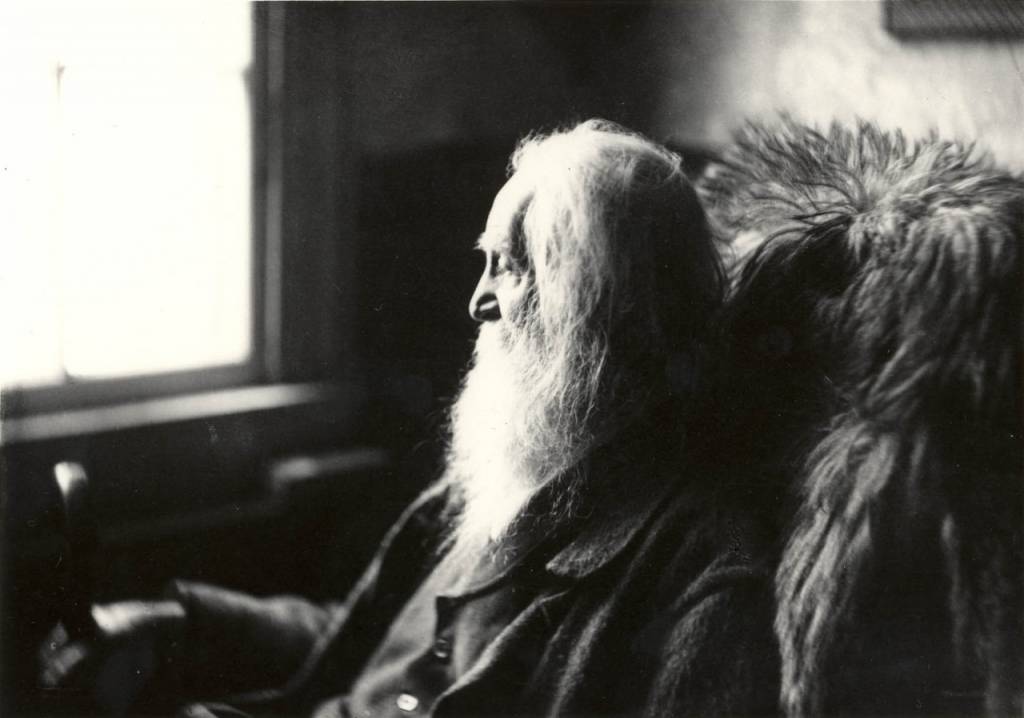

Walt Whitman, by Thomas Eakins, 1887. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Whitman became a subject of oil portraits, photographs, and busts later in his life, including a portrait by Thomas Eakins in 1887 (above). Whitman praised Eakins’s personality and paintings for pushing against politeness to depict plain truth, unlike other artists, such as Herbert Gilchrist in his 1887 portrait of Whitman, who stuck firmly to tradition. This trait that Whitman admired in Eakins is mirrored in Whitman’s poetics, which ignored expectations for steady meter and rhyme, as well as in Whitman’s friendships with sculptor and photographer Samuel Murray, who took a series of photographs of Whitman, and sculptor William O’Donovan, who created a bust of the poet. These works, especially Murray’s portraits, Whitman praised for their “direct catch—no middleman,” and one of these photographs Whitman used as the frontpiece of his book, Good-Bye My Fancy, saying that “among photos it excels any, so far, in the range of its audacity.” Eakins, Murray, and O’Donovan were equally dedicated to Whitman. After Whitman’s death in 1892, the three, along with two assistants, made a death mask and a cast of the poet’s hand in his honor.

Herbert Gilchrist’s portrait of Whitman, 1887. Held in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

William O’Donovan with his bust of Walt Whitman, ca. 1891

These personal relationships and the philosophy of ut pictura poesis (“as is painting so is poetry”) shaped how Whitman thought about art. He imagined visual artworks as being poems themselves and imagined his own poems as paintings. Whitman worked to capture the vividness of visual art in language, and he mimicked the mental and emotional stimulation of an exhibition space in his organization of Leaves of Grass. In both individual poems, like “Pictures,” and longer projects, like “Song of Myself,” Whitman juxtaposes brief depictions of contemporary, historical, and imaginary scenes, resembling the tightly-packed spaces of large nineteenth-century exhibitions.

After Whitman’s poems were published, their deviation from traditional forms, passion for honesty, exploration of the full spectrum of human experience, and dedication to individualism influenced entire art movements—Modernism especially, and critic Benjamin de Casseres lauded Whitman as one of “the real fathers of the cubists and futurists.” (Click here to read de Casseres’s famous essay “Enter Walt Whitman.”) Within these movements, many artists in particular attached to Whitman’s poetry. Stuart Davis drew from the sonic landscape of jazz for his paintings, similar to Whitman’s own attention to the sounds of America in his poem “I Hear America Singing.” Inspired by Whitman’s rejection of convention, Joseph Stella dedicated himself to craft a new visual language under Futurism to depict his individual emotions. Frank Lloyd Wright, too, was influenced by Whitman, using architecture to connect individuals to each other and to nature, similar to Whitman’s use of poetry. As Marsden Hartley developed as an artist, he would refer to Whitman’s writing often as a guide to understanding himself and nature. Hartley’s landscape paintings, including Hall of the Mountain King, were a point of ecstatic spiritual connection between the individual and the universal, much like Whitman’s poetry.

Marsden Hartley (1877 – 1943)

Hall of the Mountain King, ca. 1908-1909

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Walt Whitman’s investment in the art world and desire to merge visual art and poetry changed both genres of art, giving permission to artists to explore new expressions of personal and American identities. He continues to be an influence, encouraging us to connect with ourselves and the world around us, to also be “not a bit tamed,” to sound our own barbaric yawps.