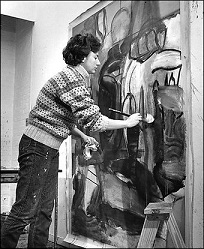

March 28 is the birthday of one of Abstract Expressionists’ leading female artists: Grace Hartigan. She was well known for her gestural, intensely colored paintings. Because she joined the movement later, she is often referred to as a “second-generation” Abstract Expressionist.

Hartigan is among a group of twentieth century female artists, including Lee Krasner and Helen Frankenthaler, whose works are all on view in the current Van Gogh to Rothko exhibition. They share a common bond in that they were often overlooked and underappreciated by galleries and museums in the male-dominated art world of their time. However, the paintings in the exhibition demonstrate that their paintings do hold up as great works of art next to the ones of their male peers.

Hartigan was born in Newark in 1922. Encouraged by her first husband, she began painting in California where the young couple got stranded on their way to Alaska. They had hoped to live in Alaska as pioneers, but never made it there. In the mid-1940’s she moved back to Newark, where she trained in mechanical drafting. She developed friendships with Abstract Expressionist painters and poets such as Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and Frank O’Hara. Hartigan used the pseudonym “George Hartigan” for her first gallery exhibition, because she felt inspired by the female writers George Sand and George Eliot. In an interview with Cindy Nemser, Hartigan denied she took the name to avoid gender discrimination. [Curtis, Cathy. Restless Ambition: Grace Hartigan, Painter, 2015. 75]

In 1950, the influential art critic Clement Greenberg and well-respected art historian Meyer Schapiro included Hartigan in their New Talent show at the Kootz Gallery in New York City, followed by a solo exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Three years later, Museum of Modern Art director Alfred Barr acquired one of her paintings for the museum collection.

MoMA included Hartigan in two major group exhibitions, 12 Americans (1956) and The New American Painting, a traveling exhibition that introduced Abstract Expressionism to Europe in 1958. She was the only female artist in that show. In May, 1957, Life magazine named her “the most celebrated of the young American women painters.”

Although an Abstract Expressionist painter, Hartigan never broke entirely with the figurative tradition. It was poet Frank O’Hara’s blending of so-called “high art” and “low art” in his poetry that inspired her to use more figuration and images from everyday life in her work. For this reason, these works are often considered precursors to Pop Art—a movement Hartigan herself actually did not like. She preferred unique, personal art generated by the evident hand of the artist over Pop’s aesthetic of mass production, advertisement, and consumerism. Hartigan explained: “I’d much rather be a pioneer of a movement that I hate than the second generation of a movement that I love.” [ William Grimes, “Grace Hartigan, 86, Abstract Painter, Dies,” New York Times, November 18, 2008, B14] After that statement, however, Clement Greenberg, who championed pure abstraction, stopped his support of Hartigan.

The re-introduction of vaguely representational imagery into her work can be witnessed in her 1957 painting New England, October, currently on view in Van Gogh to Rothko. The work reflects her expressive relationship with nature. She painted New England, October using her characteristic bold gestures and thick paint in intense colors. At first glance a non-figurative composition of an irregular grid of color patches, the work reveals, upon closer inspection, fluid landscape forms in rich autumn colors that vaguely resemble fields, hills, lakes, and buildings. The painting reflects Hartigan’s memory of a trip to Maine: “I was especially moved by Castine [Maine] … the yellows of the trees in rain, the glimpses of white colonial doorways.”

Her second work in the Van Gogh to Rothko exhibition is When the Raven Was White (1969, oil on canvas, 88 x 78 in.). It is a later work that demonstrates her move toward incorporating more recognizable imagery into her work. Sometimes these images relate to the artist’s own life. The title refers to an ancient Greek myth about a white raven that was turned black by Apollo after delivering him bad news. In 1969, the year Hartigan painted When the Raven Was White, her fourth husband became seriously ill. Even though the painting has recognizable images such as figures, flowers, and plants, it does not have a specific narrative, reflecting Hartigan’s intention to create “an imagery that would be absolutely specific but couldn’t be read in any terms of the visual world.” [Hartigan in an interview with Allen Barber, “Making Some Marks,” AM 48, No. 9, June 1974, 51] The painting is inscribed to New York art dealer Martha Jackson.

There are also two paintings by Grace Hartigan in Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection. One of them is Rough, Ain’t It. The painting evokes an urban, gritty feeling and an atmosphere full of explosive energy. Characteristic for Abstract Expressionism, Hartigan experimented with non-traditional materials and methods: she applied sand to the painted canvas to create a physical “roughness” of surface, a play on the title of her work. The curved lines of cream and black paint suggest the pouring and dripping technique associated with Jackson Pollock, and convey the Abstract Expressionists’ fascination with the effects of chance and accident. Moreover, the collage elements and layered composition evoke the early torn cardboard “combines” of proto-pop pioneer Robert Rauschenberg. The painting suggests a variety of possible interpretations, however, the title might allude to Hartigan’s nearly isolated position as a young woman working in New York’s nearly exclusively male art world, and her struggles living a life of poverty. Her belief that painting must have “content and emotion” is evident in this and her other paintings.

These three major works by Grace Hartigan illustrate her diverse career. Hartigan was respected for her commitment to authentic art and for her thick skin—and her striking paintings reflect this attitude. From 1965 on she worked at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), where she was the director of the Hoffberger Graduate School of Painting. She taught at the school until retiring in 2007, one year before she died.