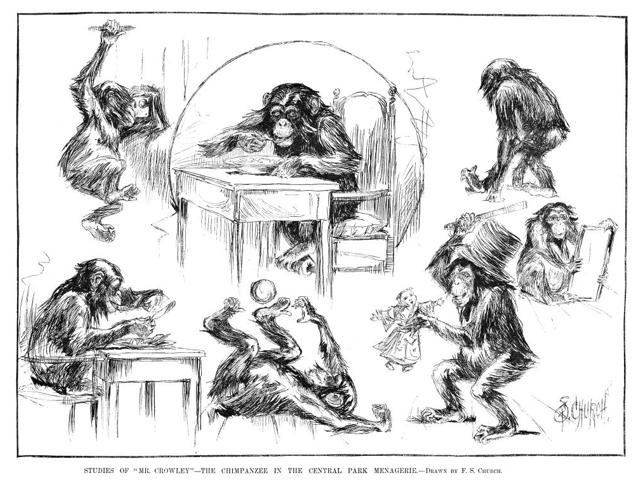

Studies of “Mr. Crowley” – The Chimpanzee in the Central Park Menagerie – Drawn by Frederick Stuart Church

A painting popular with Crystal Bridges visitors features a chimpanzee, seated in a chair, holding a copy of Charles Darwin’s 1871 classic The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Painted by James Henry Beard in 1885, the ape featured as the image’s primary subject was, in fact, a real international celebrity of the day. His name was Remus Crowley, Esq., and learning more about him, the historical context of his notoriety, and the creation of this painting, tells us much about American culture in the late nineteenth century.

James Henry Beard (1812-1893)

“It Is Very Queer, Isn’t It?”

1885

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

An 1888 booklet written by journalist Henry S. Fuller titled Mister Crowley of Central Park sheds light on the life of this remarkable chimp. Captured as an infant in Liberia, the young primate eventually found his way to New York City in 1884 at the age of six months. The director of the Zoological Collection at the Arsenal in Central Park, a man named Conklin, agreed to take the ape into its collection. In fact, Mr. Crowley, as he would come to be known, was the first chimpanzee to arrive in the United States, making him a unique specimen for study while simultaneously offering an amazing attraction for the Arsenal’s public. Conklin enlisted his assistant, Jake Cook, to serve as primary caretaker of the creature, and within months, the ape was eating with a knife and fork.

Conklin named the chimpanzee “Remus Crowley, Esquire,” after the main character in the popular 1881 book Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings: the Folklore of the Old Plantation. He claimed that the monkey reminded him of a wise soul in the vein of Uncle Remus, an African American storyteller who conveys old folk tales to children. As this was only two decades after the end of the Civil War, the question of race in America was particularly raw in the 1880s, with many racist theories of Black inferiority still strongly present in white American consciousness. Even Fuller’s description of Mr. Crowley, and the story of his life in America, are riddled with disturbing references and correspondences between the intelligence and appearance of the chimpanzee and that of African Americans. Nonetheless, Mr. Crowley’s first name fell out of common usage almost immediately.

Fuller notes a few of the notable visitors to Mr. Crowley’s chambers (including former Union General and US President Ulysses S. Grant), including a couple of artists who captured his likeness. The well-known illustrator Frederick Stuart Church (no relation to American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church) created a series of sketches that captured Mr. Crowley that Fuller included in his book. On page 108, he references the painting now featured in the Crystal Bridges collection:

In the summer and fall of 1886 [sic], Mr. J. H. Beard, the artist, made a series of studies for his full-length portrait of Mr. Crowley. This has been pronounced one of the most faithful representations. It presents him in an attitude of repose, seated in a chair with his hand resting on one hand. A volume of Darwin’s “Descent of Man” lays partly open on one side, and another of Pythagoras on the other side. On a table near are a human skull and one of a chimpanzee, which appear to have given rise to deep thought.

The portrait neither conceals his defects, nor does it magnify Mr. Crowley’s personal beauty. Some have objected to the Hamlet-like air of reverie as too great a license, but the idea has here only been applied to one of those varied moods which settles at times even on Mr. Crowley’s mercurial spirits. His early education has certainly not permitted him to become familiar with the theories pertaining to the evolution of the species, or the transmigration of the soul; but those that know him best, assert that the expression of meditation in the portrait is by no means foreign to the mobile countenance of Mr. Crowley.

Mr. Crowley died in New York in August, 1888 after battles with pneumonia and consumption. At the time, he was the longest living chimpanzee held in captivity in the United States and Europe, at less than five years. Today chimps in captivity live 40 to 50 years.

Beard exhibited the painting titled It Is Very Queer, Isn’t It at the National Gallery in New York in the fall of 1885. Over 130 years later, visitors may now enjoy it installed in the Late Nineteenth-Century Gallery in Crystal Bridges and ponder for themselves just how queer it remains to this day.

Mr. Crowley, the Chimpanzee: Mr. Crowley at Dinner, by Olive Thorne Miller

Mister Crowley of Central Park by Henry S. Fuller may be read in its entirety online through Google Books.