One of the most interesting, and challenging, parts of my job as an Interpretation Manager at Crystal Bridges involves developing engaging interactive activities for our visitors. For American Made, I had the good fortune of working with Stacy Hollander, the Chief Curator for the American Folk Art Museum, in creating the audio tour experience for the exhibition. Stacy visited Crystal Bridges in the late spring to record some sessions with me, offering fascinating insights into many objects in the show. Time and space constraints for the final product required us to cut out a lot of the great information Stacy shared during those sessions, so I decided to offer excerpts from the audio transcripts here on the Crystal Bridges blog for all to read. Enjoy! — Stace Treat

By Stacy Hollander (as told to Stace Treat during audio tour recording sessions)

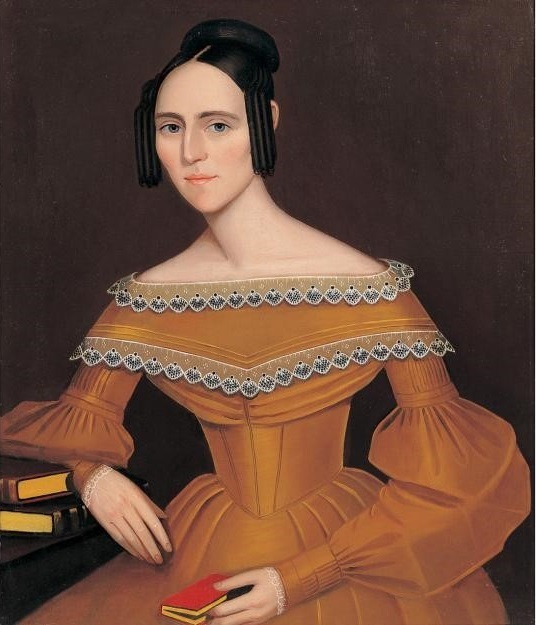

In 1924, at the height of Colonial Revival, there was a fair in Kent [Connecticut]. People brought their pictures for an exhibition. The portraits created a sensation in the art world: particularly among a generation of modern artists who were seeking an authentic American precedent for their abstract art forms. They wanted a uniquely American heritage [to draw upon for inspiration]. The paintings by Ammi Phillips (an itinerant portrait artist), who was unknown at the time, became everything for everyone at this time. As his true name was unknown, Phillips rarely signed his work, he was dubbed the “Kent Limner,” as it was in Kent, Connecticut, where these portraits were shown. “Limner” is an archaic term for a painter of faces.

Because all the portraits were painting during the same period, probably between 1830 and 1840, and because they were very similar in their presentation—in the poses used, in the props included in the portraits—it was immediately believed, and distributed through the press, that itinerant painters like Phillips painted bodies during the winter months, and during the summer months would travel and fill in the faces of the individuals. That is a myth, and it has been a very difficult myth to dispel.

It turns out that Ammi Phillips was the artist of these portraits. We still call it the Kent Period, the portraits from 1829 to 1840 or so, because they all subscribe to a certain style, to certain poses, to a certain sensibility. It has since been learned that Ammi Phillips started painting much earlier. It was advertised as early as 1809-1810 that he would paint portraits, and if you didn’t like them you didn’t have to pay for them, and he would show you in the prevailing fashion of the day. That’s an interesting statement, because Phillips painted for 55 years, until his death, and he changed his style to accord for each era in which he was painting. So his paintings of the 1810s, for instance, are appealing to the neoclassical taste: they’re beautiful, shimmering, ethereal portraits of young women in Empire-style, classically-inspired gowns, which were exquisite. Those paintings were known as portraits by the “Border Limner” because they were found in the border states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York.

Gentleman in a Black Cravat

Ammi Phillips (1788-1865)

Probably New York, Connecticut, or Massachusetts, 1835-1840

Oil on canvas

American Folk Art Museum, New York

Gift of Joan and Victor Johnson, 1991. Photos by Gavin Ashworth, New York.

Over the years, these different bodies of work were thought to have been done by four or five different artists. It wasn’t until the 1960s that it was put together that all the different portraits were the work of a single artist, Ammi Phillips. He was able to stay in business even after the era of the photograph by giving people what they wanted: by reflecting the taste of the day in terms of the size of the canvas and the presentation of the people, and also through the absolutely accurate depiction of the clothing they are wearing, the fashion of the times.

The portraits themselves represent the heights to which a self-taught artist could aspire. They are considered masterworks of American art through any lens through which you wish to apply. These portraits are different from others with a lot of props and things in background. Phillips maintained a very sparse style through the 50-odd years of his creation, but his tones changed. So in this period there are these velvety browns and blacks, and the figures emerge as jewels on black velvet. They have a light on their faces, and your eye picks out different elements in the portraits: her face and her hands and her gold dress gleam out of the darkness. And the gentleman—his shirt front, his face, and his hands. There are primary elements on the canvas that really come forward and arrest your eye as you move through these supremely balanced compositions. There’s a real sense of geometry and precision in the way in which Phillips positions his figures in the canvas. He’s also very gestural in the elements which he includes. He’s not so concerned with the reality of a scene, he’s more concerned with the composition that he’s building up; so an arm may rest on a table top, but there may not be any other indication of a table base.

American Made: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum will be on view through September 19.