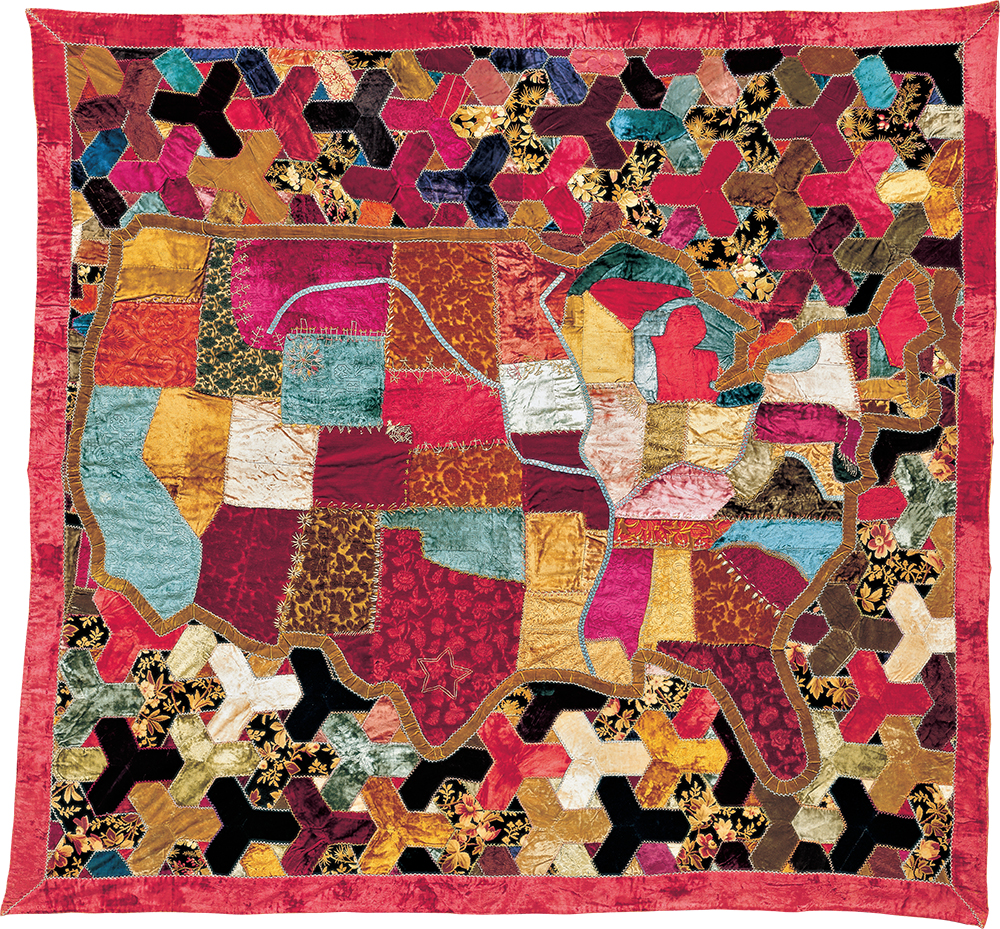

Map Quilt

Artist unidentified

Possibly Virginia

1886

Silk and cotton with silk embroidery

Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York.

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. C. David McLaughlin, 1987.

Photo by Schecter Lee, New York

One of the most interesting, and challenging, parts of my job as an Interpretation Manager at Crystal Bridges involves developing engaging interactive activities for our visitors. For the temporary exhibition American Made, I had the good fortune of working with Stacy Hollander, the Chief Curator for the American Folk Art Museum, in creating the audio tour experience for the exhibition. Stacy visited Crystal Bridges in the late spring to record some sessions with me, offering fascinating insights into many objects in the show. Time and space constraints for the final product required us to cut out a lot of the great information Stacy shared during those sessions, so I decided to offer excerpts from the audio transcripts here on the Crystal Bridges blog for all to read. Enjoy!

Stace Treat

Transcribed from an interview with Stacy Hollander, Chief Curator for the American Folk Art Museum

There’s a fairly long tradition of depictions of maps and globes in schoolgirl work. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, young girls would learn geography through art projects, whether it was drawing a map and coloring it in, or stitching a map, or creating a three-dimensional globe of the world. But it is very rare to see a map in a quilt format.

In fact, I don’t think it is immediately apparent that there is a map incorporated into this quilt because it’s so full of pattern and rich fabrics and lots of irregular pieces. That’s because this quilt comes out of what was called the “show quilt” tradition, and a subset of the show quilt tradition is the “crazy quilt.” And this map of the United States is a little bit crazy, because the delineations of the states form irregular patches by their very nature, because they’re making up a map. These are ideas in quilt-making that began to be introduced in the middle part of the nineteenth century in terms of the use of sumptuous fabrics instead of cotton, which was the usual fabric for earlier quilts. As silks became more available to wider segments of the population and women had access to these more luxurious materials, they began to incorporate them into their quilts. They were more for show, though, than utility; these were pieces that you put out when you had guests coming, that’s why so many of these pieces have survived.

That idea of using rich fabrics combined, by the time of the American centennial, with the new influences that were coming in from other countries and other cultures. In fact, one of the biggest influences seen in crazy quilts was from the at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It introduced Japanese crazed porcelains, Japanese woodblock prints, as well as ceremonies and rituals, to Americans for the very first time. Also at the Philadelphia Exposition there was a pavilion of artistic needlework from England, which was a movement that was burgeoning at the time. This was sort of along the lines of the whole William Morris idea of an emphasis on the hand arts as industrial processes were replacing the production of handmade goods. There was a reaction against that, and people wanted to reinvest in the beauty of handmade arts, so the idea of this beautiful embroidery, of handmade arts, crazed porcelains, blocks of color, all kind of came together in the idiom known as the crazy quilt.

The repeated, interlocking “Y” shape is a pattern that was published in Godey’s Ladies Book, and it was recommended that this kind of pattern work be done for small projects like pillows, little throws, things like that. So the quilt maker used those instructions to construct the background from which the map emerges, and she’s used all kinds of rich velvets, brocades, and silks to form this map of the United States.

The date is actually embroidered between the states of Oregon and Washington, in Roman numerals, and it’s 1886. There’s a yellow star in Texas, there’s a few river highlights, and some other major features of the American map. It’s not highly embellished though, so there’s always speculation that perhaps it wasn’t finished. Crazy quilts are particularly noticed for the encrusted, embellished surfaces—paintings, embroidery, appliqués, and collage—just completely covered in all kinds of embellishments, so by crazy-quilt standards, this is relatively minimal. It may be intended that way so that the map is very visible, or perhaps it was intended for further embellishment, we will never have the answer to that question.

The date is actually embroidered between the states of Oregon and Washington, in Roman numerals, and it’s 1886. There’s a yellow star in Texas, there’s a few river highlights, and some other major features of the American map. It’s not highly embellished though, so there’s always speculation that perhaps it wasn’t finished. Crazy quilts are particularly noticed for the encrusted, embellished surfaces—paintings, embroidery, appliqués, and collage—just completely covered in all kinds of embellishments, so by crazy-quilt standards, this is relatively minimal. It may be intended that way so that the map is very visible, or perhaps it was intended for further embellishment, we will never have the answer to that question.

The is another interesting thing about looking at this map of the United States in 1886. Look how large this map has grown. When we think about the original 13 colonies and the size of the original United States—and then at the end of the nineteenth century we see how vast the land is, well, the idea of Manifest Destiny comes to mind. This was an idea promulgated in the 1840s of the destiny of the United States to expand, and expand, and expand, and to spread its philosophy throughout North America. And so at the time this quilt was made, we might think of the term “Manifest Destiny” and think of the phrase “From Sea to Shining Sea.” So, whoever created this map quilt was certainly thinking of the glory of what the United States had become at this time.