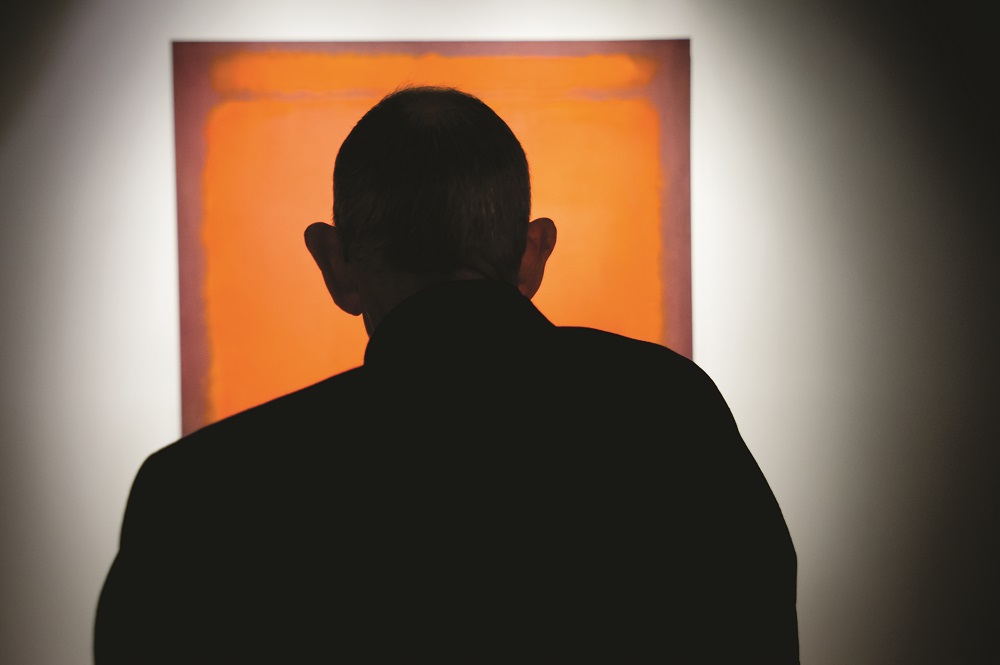

Last week we celebrated the anniversary of the birth of artist Mark Rothko, whose painting, No. 210 / 211 (Orange) is in Crystal Bridges’ collection. Painted in 1960, the canvas virtually vibrates with the interplay of the colors and shapes on its surface, and glows with an inner light that draws in the viewer. Art historian and scholar Oliver Wick captured the sensation precisely when he wrote that “The visual experiencing of Rothko’s paintings can best be described as a sensation of standing on a threshold or of reaching out into space.”[1] NOTE: While State of the Art is installed in the Museum’s Twentieth-Century Art Gallery, this particular painting is temporarily in the vault. Crystal Bridges’ guests may, however, still view Rothko’s earlier work, Greek Tragedy, which has been moved temporarily to the Early Twentieth-Century Art Gallery.

Rothko is often referred to as an Abstract Expressionist, but the artist himself saw his work differently. “I am not an abstractionist,” he famously said. “I am not interested in the relationship of color or form or anything else… I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on…. The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”[2]

The artist’s search for these peak experiences of art had begun much earlier, in the 1940s. At this time, Rothko and some of his friends and associates, including Adolph Gottlieb and Barnett Newman, were experimenting with the Surrealist style: combining representational and abstract shapes. These artists wished to look beyond the self to reveal universal truths. To this end, they had turned for inspiration to classical myth. Rothko’s 1941-42 work,Greek Tragedy, also part of the Crystal Bridges collection, evidences this earlier search for the universal through the artist’s exploration of mythology.

As he reached deeper and deeper for a means of translating that ultimate human interaction with the sublime, Rothko’s work drew further and further from representation of any kind. By 1946, all line gave way to soft blocks of color that bled into and through one another to create amorphous shapes, which Rothko thought of as “organisms with volition and a passion for self-assertion,”[3] Rothko had come to believe that “[t]he familiar identity of things has to be pulverized in order to destroy the finite associations with which our society increasingly enshrouds every aspect of our environment.”[4]

Once he had moved to this new style, Rothko began to distill his ideas, gradually stripping his work down to naked statements of form and color. From the earlier canvases of amorphous blobs he moved to the simpler “Multiforms” of the 1950s: stacked horizontal bands of color. And then eventually to the soft, diffuse rectangles that became his signature style. He stopped giving artist’s statements at this time, saying simply that “silence is so accurate.” As the style developed, Rothko’s paintings grew much larger, something the artist believed created “a state of intimacy.” “A large picture is an immediate transaction,” he said. “It takes you into it.”

To further this intimacy between canvas and viewer, Rothko became more and more obsessed with controlling the conditions in which his works were viewed. He called for the paintings to be exhibited at floor level, or no further from the floor than six inches, and he preferred that they be shown in situations that required viewers to first experience them in close proximity. He wanted to surround the viewers and, in a way, dissolve the sense of self into the experience of the work. In The Triumph of American Painting, art critic Irving Sandler wrote that Rothko desired the viewer to “vacate the active self….” and went on to point out that: “This can lead to cosmic identifications but that has a tragic dimension, for it evokes the ultimate loss of self — death.”[5]

Some have speculated that Rothko’s paintings grew increasingly dark through the later part of his career as an outward indication of the artist’s depressive inner state of mind: culminating in his suicide in 1970. (The paintings in the Rothko Chapel, for example, are so dark as to appear almost entirely black.) However, Rothko stated unequivocally that his paintings were not an expression of his own emotional state, but rather an attempt to connect his viewers with the sublime.

“The progression of a painter’s work, as it travels in time from point to point, will be toward clarity: toward the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer,” he said.[6]

Just as his compositions became more and more simplified as he continued to reach for this goal, it makes sense that his choices of colors might also have become “clarified,” honed down gradually to black. Black might be considered the ultimate purity of color—ideal, perhaps, for contemplation of large, universal truths. For Rothko, black—which can be seen as both the absence and presence of all color—might have been, like silence: “so accurate.”

[1] Oliver Wick, “Mark Rothko, ‘A consummated experience between picture and onlooker’” [2} Conversations with Artists, Selden Rodman [3] Mark Rothko, “The Romantics Were Prompted,” Possibilities (Winter 1947-48), no. 1 [4] ibid [5] Irving Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism [6] “Statement on his Attitude in Painting,” from Tiger’s Eye, no. 9, October 1949.