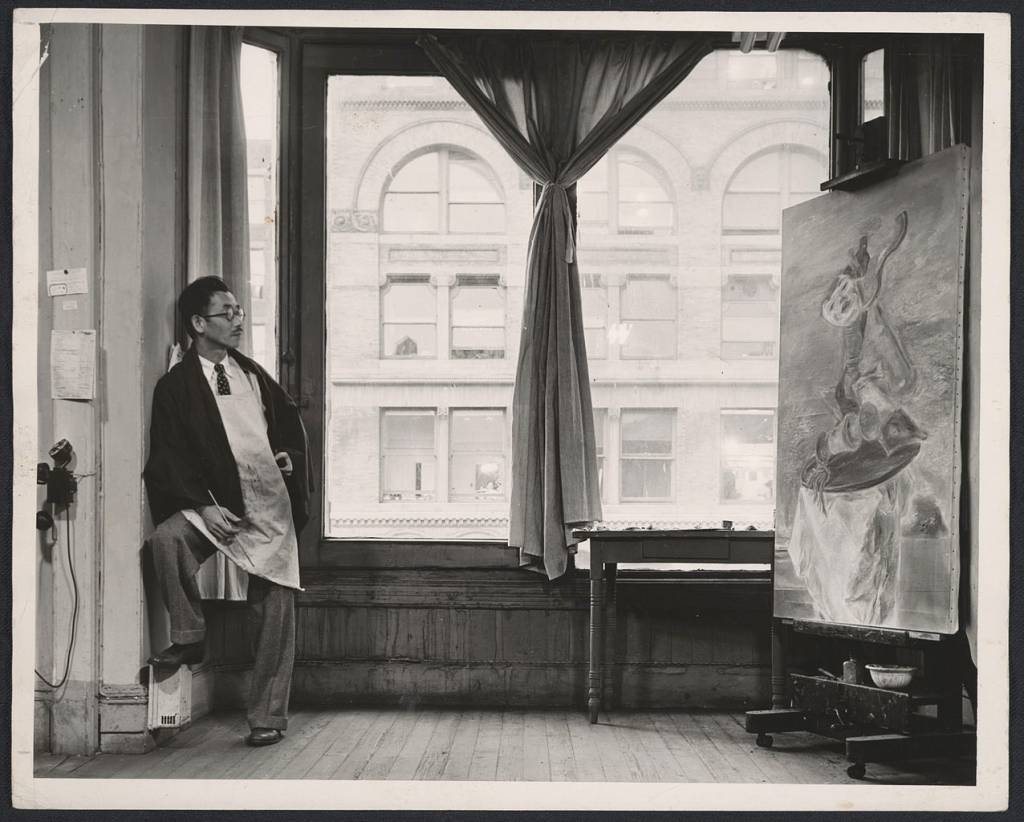

Kuniyoshi in his studio, at 30 East Fourteenth St. in New York, N.Y., photographed by Max Yavno for the Federal Art Project Photographic Division.

The United States is an unusually diverse country, built and populated by immigrants from every nation in the world. Despite this, throughout American history, immigrants have also been the targets of discrimination, prejudice, and bigotry. Different ethnic or racial groups have been the primary targets at different times, but they run the gamut: Blacks, Jews, Chinese, Muslims, Japanese, Irish, Germans, Middle-Easterners, French, Native Americans… the list goes on. Yet without the contributions of these groups, our country would not, could not, be what it is today.

To celebrate our immigrant heritage, throughout September we’re going to publish some longer posts that showcase some of the wonderful immigrant artists whose works are included in Crystal Bridges’ collection of American art. Beginning with this one written by curatorial intern Gabi Andino. Enjoy! –LD

Today we’d like to take the time to celebrate the life of Japanese artist and photographer Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who was born this day in 1893, and whose work we are grateful to house in our permanent collection and exhibit in the Early Twentieth-Century Gallery. Kuniyoshi was a disciplined, thoughtful, and engaged leader of the Modernist movement in America, while simultaneously navigating the fragile circumstance of being a Japanese immigrant during World War II. His life and career revolved around an entirely personal expression of identity and acute psychological states. It is arguable that Kuniyoshi was one of the most exceptional members of American Modernism in New York City from the 1920s into the late 1940s.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, (1889 – 1953)

Little Joe with Cow, 1923

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

An Unexpected American Artist

Yasuo Kuniyoshi was born in the southern province of Okayama, Japan, on this day in 1889. The Japanese-American artist lived and worked in the United States for a majority of his life, from approximately 1906 until his death in 1953.

To avoid serving in the Japanese military, Kuniyoshi asked his father for permission to immigrate to the United States, by himself, at the age of 16. When Kuniyoshi left for America, he had no compelling goals and was only planning on staying in the country for a few years. At this time, he had no idea where his future would take him or how his Japanese identity would impact his life and work.

“Looking back…one can see that it [Kuniyoshi’s art] was among the most original products of the modern movement” – Lloyd Goodrich, “Kuniyoshi” (1948)

While growing up in Japan, America was talked of as a land of opportunity. His first job was in a railroad yard in Spokane. Here he saw hundreds of fellow Japanese immigrants living in tents and sleeping on straw. After only a few days on the job, he chose to work instead as a porter in an office. By 1907, he had saved enough money to move to Los Angeles. It was here that a high school teacher suggested Kuniyoshi study art after watching him produce a rendering of a map of China. So, Kuniyoshi enrolled in an academic drawing course at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design. He liked it so much that he dropped out of public school to focus on studying art.

In 1910, Kuniyoshi moved to New York City. After years of nomadic existence and jumping from school to school, Kuniyoshi found his artistic home from 1916 to 1920 at the Art Students League, where he studied under Kenneth Miller Haynes and worked alongside fellow students Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, and Alexander Calder. In 1917, he exhibited for the first time at the Society of Independent artists. Kuniyoshi’s first one man show was held in 1922 at the Daniel Gallery in Manhattan.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, “The Calf Doesn’t Want To Go” (1922), ink on paper (courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, © The Museum of Modern Art

My Country My Enemy: Japanese Identity, Discrimination, and WWII

In the summer of 1919, Kuniyoshi married Katherine Schmidt, who then lost her American citizenship for marrying an Asian man. Asian immigrants were not allowed to become naturalized American citizens, and the passage of the Immigration Act in 1924 further deepened systemic discrimination against Asian immigrants in general and those from Japan in particular, as it effectively banned further immigration from Japan. When, in 1929, Kuniyoshi was selected as one of “19 Living Artists” exhibited at MoMA, his inclusion in this group exhibit brought controversy surrounding whether or not he was “American,” though he had been living in the country for more than 20 years.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Katherine Schmidt at a costume party in their house in 1925, photograph by Stowall Studios. Rosalie Berkowitz collection of photographs, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and America’s entry into WWII affected the mood of Kuniyoshi’s artwork. His compositions and subjects became more complex and frequently showcased landscapes of ruin. At this time, Japanese Americans were classified as “enemy aliens,” and more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent along the US West Coast, whether or not they were citizens of the United States, were rounded up and interned. Japanese on the east coast were not interned, but Kuniyoshi’s camera was taken from him, his bank accounts were frozen, and he was prohibited from traveling outside of the New York area. With the closure of the Daniel Gallery in 1931, photographing artwork was Kuniyoshi’s main source of income during this time. With a lack of agency in creating business for himself, Kuniyoshi supported himself by teaching at the Art Students League and creating commissioned, anti-Japanese posters for the Office of War Information. In this way, Kuniyoshi grappled with conflicting feelings about his place within the culture of his adopted homeland.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1889–1953),

Pencil on paper, 40 x 28½ inches.

Collection of John Cassara. © Estate of Yasuo Kuniyoshi

Kuniyoshi’s Legacy

Despite being discriminated against in his personal life, Kuniyoshi’s professional impact in the art world was not overlooked. Kuniyoshi became the first elected President of the American Artist’s Group, was on the executive committee of the American Artists’ Congress, received an artist’s fellowship from the Guggenheim, and was awarded first prize at the Carnegie Institute in 1944.

The first-ever retrospective of a living artist at the Whitney was held in his name in 1948, five years before his death. Lloyd Goodrich, previously a fellow student with Kuniyoshi, curated the exhibit and wrote: “The strength and virtue of Kuniyoshi’s art have always lain in its deep sensory vitality. As he has grown older this vitality…has become more complex, rich, and subtle. His art…has the combined ripeness and refinement of maturity.” – from “Kuniyoshi” (1948)

“Skill is nothing. Anyone can be skillful. Skill is a means to an end. What you want to say is more important than skill” – Yasuo Kuniyoshi (as recalled by his students)

Yasuo Kuniyoshi was a thoroughly disciplined artist with a rich inner world. His lived experience of being simultaneously Japanese, American, and an artist trying to harmonize multiple identities amidst war and rejection continues to be inspirational. In 2015, the Smithsonian Museum of Art curated an exhibit to observe Kuniyoshi’s contributions to American art. This was the first comprehensive retrospective of the artist’s career since 1948.

We encourage readers and especially Modernist enthusiasts to explore the online exhibit published by the Smithsonian here*

Yasuo Kuniyoshi

Island of Happiness

1924

Oil on canvas

24 x 30 in. (60.9 x 76.2 cm)

Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

Art © Estate of Yasuo Kuniyoshi

Sources Cited:

“Exhibitions.” Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery. 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017. http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/online/kuniyoshi/index.cfm.

Goodrich, Lloyd. Yasuo Kuniyoshi. New York: Macmillan, 1948.

Kuniyoshi, Kuniyoshi. A special loan retrospective exhibition of works by Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Gainesville: University Gallery, University of Florida, 1969.

Meier, Allison, Ben Valentine, Lyric Prince, Benjamin Sutton, Claire Voon, Matthew Harrison Tedford, and Mary Louise Schumacher. “Yasuo Kuniyoshi Retrospective Places the Painter at the Center of Modern Art in the US.” Hyperallergic. July 22, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017. https://hyperallergic.com/220340/Kuniyoshi-kuniyoshi-retrospective-places-the-painter-at-the-center-of-modern-art-in-the-us/.

Stamberg, Susan. “The Anxious Art Of Japanese Painter (And ‘Enemy Alien’) Yasuo Kuniyoshi.” NPR. August 13, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017. http://www.npr.org/2015/08/13/430374356/the-anxious-art-of-japanese-painter-and-enemy-alien-Kuniyoshi-kuniyoshi.