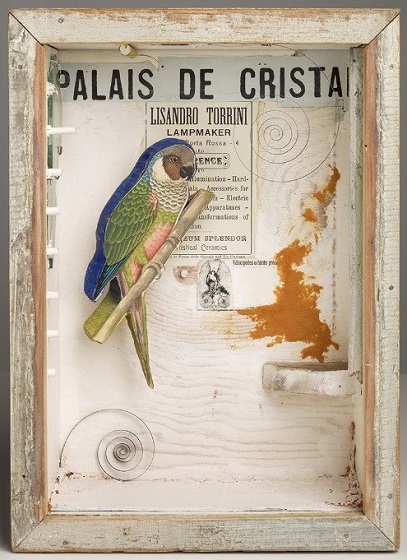

Joseph Cornell

Untitled (Palais de Cristal), ca. 1953

Wood box construction: printed-paper collage, glass, and metal

13 in. × 9 1/4 in. × 4 1/4 in. (33 × 23.5 × 10.8 cm)

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, 2014.28. Photography by Edward C. Robison III.

This is the first week to view a very exciting addition to Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection. Untitled (Palais De Cristal), by Joseph Cornell, is a shadowbox featuring a print of a bird encased in glass. It is currently on view in our recent acquisitions niche in the Colonial and Early Nineteenth-Century Gallery: the first gallery most guests enter at the Museum. This small-scale work is a fascinating example of Cornell’s unusual approach to making art. Let’s dive into what makes this artist and his work so interesting.

Joseph Cornell’s Grand Tour

During his 69 years on earth, Joseph Cornell never left the United States and hardly ventured beyond New York City. However, through collecting everyday objects with no inherent worth, he traveled vicariously to foreign places and distant times. Today, through his enduring artwork, Cornell continues to take us with him.

While he had no formal training in art at all, and could neither draw nor sculpt, Cornell was a part of elite artistic circles during his lifetime, garnering praise from artists like Marcel Duchamp, Robert Motherwell, and Andy Warhol. He was seen as a progenitor of American Surrealism and the medium of collage—what one critic called “paste, applied to waste, with taste.”

The artist’s prolific career began with his wanderings in the city, during which he escaped to thrift shops and cultural centers and soaked up all the information he could. From these forays, began to do further research and collect items related to world culture and history. During one of his explorations into the city in the early 1930s, Cornell happened into the gallery of Julian Levy, the first promoter of Surrealist art in America. Within a few months, with Levy’s help, Cornell exhibited his work at an important Surrealist show. By 1940, he committed himself entirely to art and set up a studio in his basement where he constructed and organized his own private universe of ephemera in whitewashed boxes labeled in midnight-blue paint.

Royal Academy of Arts. “Cornell’s basement studio, 3708 Utopia Parkway, Flushing, New York, 1964”

Collection Duff Murphy and Janice Miyahira © Terry Schutté. Accessed August 23, 2016.

Cornell principally loved collecting items relating to the nineteenth-century tradition of the “Grand Tour” of continental Europe. As a rite of passage into adulthood, artists and wealthy young men of the time, mostly British, set out with a standard itinerary in order to discover the essence of Western civilization. From his research and collecting, Cornell’s artwork created Grand Tours of Europe on a micro scale. He was so well-versed on European cities, from his “armchair traveling,” that when he first met Marcel Duchamp, as the story goes, they talked at length in French about Paris, winding their way from the opera house to the galleries of the Louvre to the lobbies of the grand hotels. At the end of the conversation, Cornell mentioned he had never seen the city in person, leaving Duchamp speechless.

Cornell’s collections-turned-artworks allowed him to comment on the European history of collecting and the beginnings of museums, which can be traced to the sixteenth-century “cabinets of curiosities” kept by wealthy families that showcased a range of objects, including art, relics, and scientific specimens—creating a world in miniature. In a similar fashion, Cornell curated and arranged his collection for viewing, and created his own encyclopedic museums to elevate the mind and soul.

Imagination Takes Flight

Untangling the myriad deliberate associations in Cornell’s boxes can be important for understanding the artist, but the work is not meant to be “decoded” into one set meaning. Cornell instead creates a stage for the viewer to come up with their own stories and imaginary travels.

Untitled (Palais de Cristal) draws on the artist’s interest with European history and dreams of travel. The words Palais De Cristal, or Crystal Palace, reference an architectural marvel built by Joseph Paxton for the first World’s Fair in London in 1851, which was seen as the true beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. Glass, windows, mirrors, and architectural feats fascinated Cornell, and we can see him playing with this in his glass-covered shadow boxes, creating windows through which we may view his world.

Arch Expo. “The Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, 1851.” Colored lithograph by Augustus Butler © Science & Society Picture Library/Getty Images. Accessed August 23, 2016.

Birds are a reoccurring motif relating to travel in Cornell’s work. The artist was deeply moved after he saw caged tropical birds in a pet shop, which inspired his aviary series. After Cornell got a bicycle and was able to travel to more rural places, he became an amateur naturalist and birdwatcher. Historically, birds were often kept by rulers as prestigious pets or displayed as trophies of voyages to distant worlds. He saw flight as a positive symbol of pure spirits able to travel vast distances at will.

Interestingly, Cornell seemed content to only dream of travel. As he became more well-known in the 1950s, success would have provided him with means to go abroad, but he didn’t. Like seeing beautiful things inside a glass box that we cannot touch or use, yearning to experience was Cornell’s subject matter more than the experience itself.

Joseph Cornell simply did not see boundaries between high art and pop culture, old and new, science and art, and space and time. Although his work was cutting edge in the art world, unlike many radical avant garde artists, he was not trying to challenge views of normal life. Instead he wished to communicate the wonder he found in daily existence and the richness of human culture, showing us all the endless power of the imagination.

Listen to a Spotify playlist of some of Joseph Cornell’s favorite music: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/listen-to-joseph-cornells-record

Works Cited:

Royal Academy of Arts. “Curator Sarah Lea discusses ‘Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust.’” Accessed

August 23, 2016. https://audioboom.com/boos/3584145-curator-sarah-lea-discusses-joseph-cornell-wanderlust.

Royal Academy of Arts. Joseph Cornell Wonderlust. London: Royal Academy of the Arts, 2015.