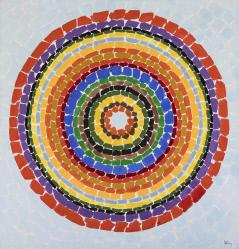

“Lunar Rendezvous—Circle of Flowers,” 1969

Alma Thomas, 1891 – 1978

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

It may not surprise you to learn that many of the people who work in various capacities at Crystal Bridges are practicing artists in their own right. After all, it makes sense that artistic, creative people would be interested in working in the vicinity of great works of art; and plenty of artists who are well known today began their careers in some museum side-line while they honed their technique. Kerry James Marshall, for example, worked for an art moving company, and talked about the value of that work when he visited Crystal Bridges in 2015.

“If I had to have a job that I had to punch a clock on, (art moving) was the best job I ever had, never enjoyed going to work more,” he told us. “It’s everything. At packing and crating at the time, everybody did everything. Everybody built crates, everybody drove the truck, everybody did pick-up and delivery, everybody did installation. So you got to go in, see behind the scenes at every museum. You got to handle the stuff too…. Then you got to see it in the homes of the rich and famous, you go to do all of that. You got to go to the studios of the artists and pick up the stuff. You see everything and you talk to everybody and people become familiar with you in that place.”

Very few people are born at the top of their game. Amadeus Mozart and other child prodigies aside, almost everyone else has to grow into their art, and it happens at different rates for different people. Some artists peak early, some peak later, and some don’t even enter the game until middle-age or later. There’s no standard timeline, no set of prescribed steps one has to take.

I think the fresh, bright beginning of a brand new year is a good time to be reminded that it’s never too late to become what you want to be. So, on that theme, I present to you some encouraging stories of great American artists who got a late start.

“Lunar Rendezvous—Circle of Flowers,” 1969

Alma Thomas, 1891 – 1978

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Alma Thomas (1891-1978) didn’t devote herself fully to her art career until she retired from teaching at age 69. In 1972, at age 80, she was the first African American woman to receive a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum.

Janet Sobel, 1894 – 1968

“Hiroshima,” ca. 1948

Oil and enamel on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Janet Sobel (1894-1968) did not begin painting until she was 45, and yet her work was featured in a series of New York’s top galleries by 1944, and very likely helped to inspire the groundbreaking “drip and splatter” style of painting adopted by the young Jackson Pollock.

Photo by Marc F. Henning

Louise Bourgeois’ “Maman” sculpture on Aug. 5, 2015, at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Ark.

Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), creator of the monumental spider sculpture, Maman, in Crystal Bridges’ courtyard, was 71 when she had her first one-woman show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (the first female artist to be accorded such an honor) in 1981.

There are also plenty of artists who started their careers as something else completely:

William Wetmore Story (1819 – 1895)

“Sappho”

modeled 1862, carved 1867

Marble

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

William Wetmore Story (1819-1895), whose lovely sculpture of Sappho adorns Crystal Bridges’ Colonial and Early Nineteenth-Century Art Gallery, was a Harvard-trained lawyer before he chucked it all to move to Rome and become a sculptor.

Francis Guy (1760 – 1820)

Winter Scene in Brooklyn, 1820

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Francis Guy (1760-1820) was a silk-dyer in London. In 1795 he moved to the United States to ply his trade in Baltimore, but his shop burned down in 1799. With no formal training, he turned instead to painting, and is now considered one of America’s most important early landscape artists.

And then there were those who failed at everything BUT art:

John James Audubon, 1785 – 1851

Wild Turkey Cock, Hen and Young, 1826

Oil on linen

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

John James Audubon failed as a farmer, a merchant, a gristmill owner, a taxidermist, and a teacher of dancing and fencing before he began the art career that would turn him into an American household name.

Samuel F.B. Morse (1791-1872)

“Marquis de Lafayette”

1825

Oil on canvas

Even though he studied art at the Royal Academy in London, Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872) putzed around trying to decide what to do with his life for some time after his return to the US. He worked as an itinerant portrait painter and tried to become an inventor (before his famous telegraph invention). He even went to divinity school for a time before he got serious about painting. Today, several of Morse’s artworks are well respected, including the portrait of LaFayette in Crystal Bridges’ collection, but the artist became frustrated with the lack of sophistication of the early American art scene. He gave it up, later becoming better known for his invention of the single-wire telegraph system and Morse code.