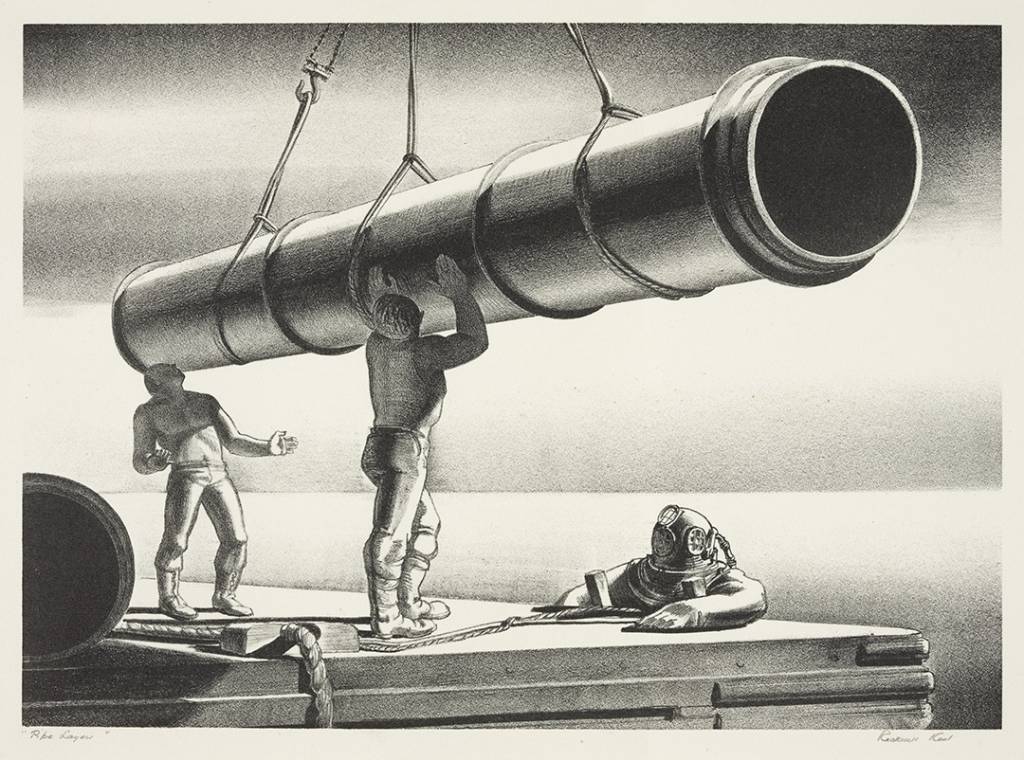

Rockwell Kent, 1882 – 1971

Big Inch, 1941

Lithograph

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

In honor of May Day: traditionally a celebration of Labor in many European countries, we will take a look at some works on paper in Crystal bridges collection that celebrate the American labor movement. The museum’s permanent holdings includes a collection of 468 prints made by American artists between 1925 and 1945. Many of the artists represented are familiar to Crystal Bridges’ visitors, including Thomas Hart Benton, Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, Reginald Marsh, and Charles Sheeler.

Thomas Hart Benton

Construction, 1929

Lithograph

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Not long after Franklin Delano Roosevelt inaugurated the Works Progress Administration in 1935 to create jobs for unemployed Americans, he was contacted by artist and former classmate George Biddle who pointed out to the President the plight of American artists. Roosevelt, though he was not particularly an art enthusiast himself, realized that artists, too, needed opportunities for work. He founded the Federal Art Project, which included divisions for visual artists, as well as for writers, musicians, and performing artists.

Holger Cahill, who directed the Federal Art Project, was interested not only in providing gainful employment for out-of-work artists, but in bringing art back into the lives of average men and women, and to “help heal the breach between artist and public that has become distressingly evident in the contemporary period.”[1]

The goal of the project was to create “art for the people,” through public art projects, exhibitions, and classes. Probably the best well-known of the FAP projects are the large murals that now grace post offices, schools, and other public buildings across the country (including those by Thomas Hart Benton in the Missouri State Capital in Jefferson City, MO). The WPA poster project turned out posters with bold graphics advertising the projects and programs of the performing branches of the FAP, as well as other WPA projects such as the Civilian Conservation Corps. The printmaking artists were part of a branch of the FAP known as the Graphic Arts Division, whose first studio opened in New York City in 1936.

Samuel L. Margolies, 1897 – 1978

Men of Steel, 1940

Drypoint

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Because prints were portable and multiple, they were easy to distribute around the country. The government sent packets of FAP prints to schools, libraries, hospitals, and other tax-supported institutions across the country, and the prints were also sold inexpensively to the public at large. This meant that, for the first time, average working Americans were able to afford original works of modern art.

FAP printmaker Harry Gottlieb said: “American people cannot afford oil paintings, or even watercolors, yet they want pictures in their homes. The sharecropper tacks up pictures from the Sunday paper; screen prints can provide an art that people can afford to buy.”

Artists of the FAP were naturally drawn toward scenes that dealt with the real-world situations of the day—the Depression, bread lines, increasing tension between the upper and middle classes, and the social changes produced by the rapidly increasing industrialization of the country. These were the subjects of the working class, and the printmakers—highly skilled artisans who worked with their hands— identified strongly with these fellow laborers. There are a number of prints that deal with the Depression head-on and picture working-people hard at work trying to improve their circumstances.

Edward Hopper, 1882 – 1967

The Railroad, 1922

Etching

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Prints and Labor Politics

Printmaking was also a vehicle for spreading political and social messages. Images make powerful statements, and many of the images in this collection are quite outspoken in their criticism of the capitalist system that fueled the country’s economic collapse. There are images emphasizing big industry’s disregard for the human laborers who keep the industries going, as well as its negative impact on human living conditions and the environment as a whole. At the same time, labor itself is celebrated, with human figures shown as muscular, powerful individuals capable of building and manipulating the industrial machinery they operate.

Letterio Calapai, 1902 – 1993

Labor in a Diesel Plant, 1943

Woodcut

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Artists’ identification with labor soon led to political and social activism among the artistic community. Artists who had previously always worked in isolation now found strength in numbers. In 1934 the Artists Union was formed to agitate for better pay and working conditions for artists in the FAP’s employ, and to lobby against cuts in funding. The Artists Union was also a powerful supporter of labor rights in general, often adding their presence to picket lines for other industries. The American Artists’ Congress was formed in 1936 as part of the Communist Party’s Popular Front. Artists of many different political stripes came together through this organization to promote democracy and civil liberties, lobby for government support of the arts, and to combat fascism and censorship. Through solidarity, the climate changed from one of despair to one of empowerment and of hope for a more equitable and democratic future.

Boris Gorelick, 1912 – 1984

Sweatshop, ca. 1935

Lithograph

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Books About the Federal Art Project in the Crystal Bridges Library

The library is open for all visitors during museum public hours. Come up to the third floor during your next visit to browse the shelves and enjoy the terrific views of the museum campus from the wall of windows!

Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, edited by Francis V. O’Connor. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C., 1972

When Art Worked: The New Deal, Art and Democracy, by Roger G. Kennedy. Rizzoli, New York, 2009.

The New Deal Art Projects: An Anthology of Memoirs, edited by Francis V. O’Connor. New York Graphic Society, Boston, 1973

New Horizons in American Art, with an introduction by Holger Cahill, National Director, Federal Art Project. New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1936.

Depression Printmakers as Workers: Redefining Traditional Interpretations, by Mary Francey, Utah Museum of Fine Arts, 1988.

Notes

[1] Holger Cahill, from the introduction to the catalog for the exhibition New Horizons in American Art, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1936.

[4] When Art Worked: The New Deal, Art and Democracy, by Roger G. Kennedy

This article is excerpted from a story that was first published in C magazine, Crystal Bridges’ membership publication, in 2013.