Today is the birthday of American artist and inventor Samuel F.B. Morse. In recognition, Crystal Bridges’ Interpretation Manager Aaron Jones spools out a fascinating and complex yarn of art, technology, heroism, tragedy, and transcendence for your enjoyment –LD

Among the distinguished paintings exhibited in Crystal Bridges’ Colonial and Early Nineteenth-Century Art Gallery is portrait study of a man with strong features titled Marquis de Lafayette. Painted by Samuel F. B. Morse in 1825, the loosely painted composition stands in contrast with the neighboring grand manner portraits of recognizable leaders of the United States. However, you may be surprised to learn that the contributions made by both the sitter and the artist continue to impact our lives today.

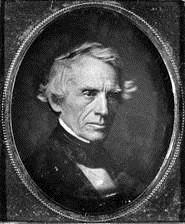

Born in Charlestown, Mass. on 27th April 1791, Samuel Finley Breese Morse sought to become a professional portrait artist. A Yale University graduate, Morse continued his studies at the Royal Academy under Benjamin West. Upon his return stateside, Morse’s future looked promising. He received commissions to paint portraits of former Presidents John Adams and James Monroe, as well as a series of allegorical works to hang in the halls of Congress. However, it was the commission to create a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette that Morse believed would catapult his career.

Marie Jean Paul Joseph Roche Yves Gilbert du Motier Marquis de Lafayette (we’ll just refer to him as Marquis de Lafayette) was a French general and political leader who enthusiastically supported the American Revolution before France had officially entered into an alliance with the United States. At the age of 19 he came to America and fought alongside George Washington throughout the Revolutionary War. Wounded at Brandywine in September 1777, Lafayette endured the miserable winter at Valley Forge with Washington and his troops and played a critical role in the ultimate victory of the Revolutionary War, co-leading American forces in the successful siege of Lord Cornwallis’s British armies at Yorktown.

In 1824, Lafayette returned to America to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the American Revolution. Invited by President James Monroe as an honored guest, Lafayette toured all 24 states during his visit. Amidst the celebration of the general’s visitation, citizens of the United States renamed streets, town squares, and communities in his honor. Interestingly, Fayetteville, Arkansas was named (indirectly) after General Lafayette. Don’t believe me, Kevin Bacon? Well, here are your three degrees of separation…

“Fayetteville” was originally known as “Washington,” Arkansas because the county seat was located in Washington County. The name was officially changed in 1829 by postmaster Larkin Newton to avoid confusion with the town of Washington of Hempstead County in south Arkansas. “Fayetteville” was chosen as the name because two of the city commissioners were both from Fayetteville, Tennessee. Established in 1809, Fayetteville, Tennessee was named after Fayetteville, North Carolina, from which the majority of the early residents of the city derived. 1783, after the Treaty of Paris was signed, officially ending the American Revolutionary War, the town of Campbellton, North Carolina changed its name to Fayetteville in honor of General Marquis de Lafayette. Salute!

But our familiarity does not end with the illustrious name of the Marquis. Due to his innovative techniques and style of painting portraits, the City of New York commissioned Samuel Morse to paint a portrait of Lafayette. Honored for the opportunity, Morse felt compelled to paint a full-length, grand manner portrait (completed in 1826, the portrait currently hangs in New York City Hall). To capture the distinct facial features and details of the Marquis, Morse painted a loose and gestural bust-study from life. This portrait study is the work featured in the Crystal Bridges collection. While working on the study of the Marquis, Morse received a letter from his father–delivered via horse messenger–that his wife, Lucretia, was gravely ill. Morse left the capital and raced to his Connecticut home. Unfortunately, by the time he arrived, his wife had not only passed—she had already been buried. Devastated that it had taken days for him to receive notification of his wife’s illness, Morse began to search for a means of improving the state of long-distance communication while simultaneously pursuing his artistic career.

During one of his European travels, Morse overheard a shipboard discussion on electromagnets as a means of communication. This led to the invention for which he is most widely known. The artist-turned-inventor developed an alphabetical system that could transmit messages through a single wire telegraph. He called this system….Morse Code. On May 24, 1844, the first message to travel by the electric telegraph was sent from the Supreme Court Room in the Capitol in Washington D.C. to the railway depot at Baltimore. The message: “What hath God wrought.”

The telegraph was the first practical use of electricity, and the forerunner of today’s e-mail. In 1845 Morse’s invention notably achieved its intended purpose—delivering a message to the recipient when time was of the essence. In Slogh, England, a woman was found murdered in her home. The assumed culprit was John Tawell, a married man with whom she was having an affair. Tawell fled by train to London and would have escaped, except authorities used Morse’s invention to send a message to London describing the accused. Tawell was apprehended, tried, convicted, and ultimately hanged. He is considered the first criminal to be apprehended due to advancements in telecommunications.

Every painting has a story to share. On your next visit to the Museum, it is our hope that you make a meaningful connection with the works in our collection.