Across the nation, individual city governments are renaming Columbus Day as Indigenous People’s Day. As of 2017, 525 years have passed since the landing of the Santa Maria upon the beaches of what is now the Dominican Republic. Today, we would like to recognize and celebrate the strength and endurance of Indigenous nations and peoples who are still here and continuing to create culture and disseminate knowledge throughout not just America, but the entire world.

Next fall, Crystal Bridges will premier the exhibition, Native North America (working title). One artist featured in the exhibition is First Nations artist Carl Beam (Ojibwe, 1943-2005). Beam made Indigenous history when the National Gallery of Canada bought his work The North American Iceberg in 1986. This transaction marked the first time the institution had acquired a contemporary artwork by an Indigenous artist, and it set a precedent for future museums to accept and display a more diverse range of perspectives and artists.

Carl Beam (Ojibwe, 1943-2005)

Burying the Ruler #1 (1991)

Photo emulsion and acrylic on canvas

Carl Beam was a successful working artist for over 25 years in the late twentieth century. Born in M’Chigeeng First Nations in 1943, Carl was called “Ahkideh” by the elders while growing up, which means “one who is brave” in the Ojibwe language. His creative talents were recognized at a young age and he moved on to pursue art and ceramics at the Kootenay School of Art in 1971 and later received a BFA from the University of Victoria in 1974. After completing several graduate-level credits, Beam moved back to Ontario.

Beam was proficient in a variety of photographic methods, as well as oil, acrylic, pottery, earthworks, Plexiglas, stone, cement, wood, and found objects, and also printing processes like etching, lithography, and screen printing. His imagery purposefully extended between and across personal, tribal, and global references to express the conglomerate nature of contemporary living.

Carl Beam (Ojibwe, 1943-2005)

Bowl with Interior Decorated with Mother Teresa (1982)

Natural mineral pigment on unglazed earthenware.

Gardiner Museum, Toronto

In memory of Margaret and Josef Erdle, Gardiner Museum

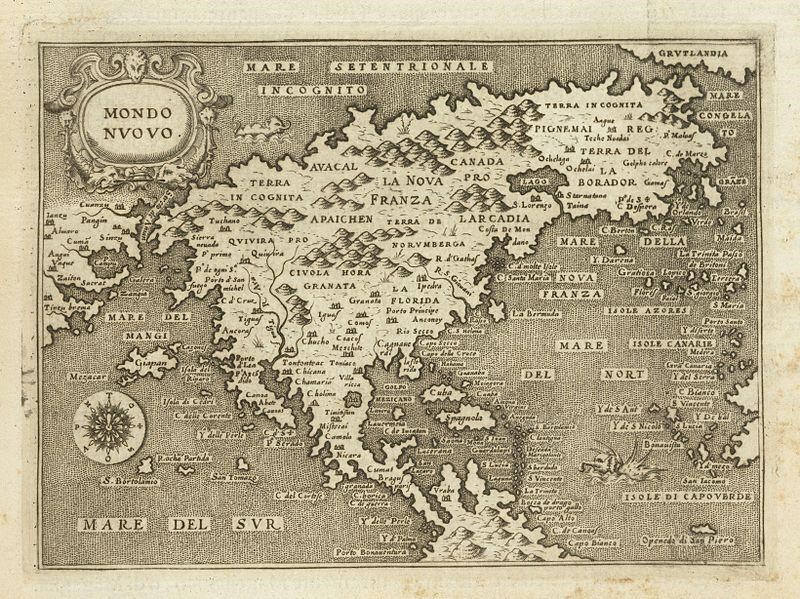

One of Beam’s more famous series of works is the Columbus Chronicles. From 1989 to 1992, around the 500th anniversary of the landing of Columbus in the West, Carl Beam created a large body of works that confront stereotypes concerning the legacy of Christopher Columbus and the effects of colonization in the Americas, specifically the effects of Native American displacement and genocide. The series traveled to international art venues in Italy and the United States.

Carl Beam (Ojibwe, 1943-2005).

Columbus Chronicles (1992)

photo-emulsion, acrylic, graphite on canvas

National Gallery of Canada

The large painting is over eight feet tall and addresses the artist’s calculated response to different versions of history and the fluid nature of culture. To explore elements within the Columbus Chronicles in closer detail, please follow the link below:

Examine the Columbus Chronicles in closer detail

The photographic images on the canvas include traffic lights, bees, a portrait of Christopher Columbus and a Native American chief connected by a five-dollar bill, and a stencil of the word HIROSHIMA in white paint in the top left corner. All of these elements have been poured over with white acrylic paint to suggest that the aftermath of Europeans coming to the West had the same devastating effects to Indigenous nations as the atomic bomb did in Japan. The seemingly out-of-place images that Carl Beam employs are read as part of his message, or worldview, which is spelled out through the usage of these glyph-like images. The collage elements of the work along with his expressive paint pouring are similar to the techniques and style seen in the work of Robert Rauschenberg.

Carl Beam continued to merge aspects of his contemporary worldview in collaboration with his Indigenous heritage as a means to challenge the colonizer’s perspective of history. He called this the “trickster shift.” His inclusion in the collection at the National Gallery of Canada was just one—however monumental—step in integrating colonial and Indigenous representations of reality. In hindsight, Beam said that he “…realized that when they bought my work it wasn’t from Carl the artist but from Carl the Indian. At the time, I felt honored, but now I know that I was used politically.” (Beam, inDion & Salamanca, p.166)

Today, Carl Beam’s work, along with art by many other Indigenous artists, is on display in museums across the North American continent. Our upcoming exhibition Native North America (working title) will feature Beam’s Columbus Chronicles, among many other works by Indigenous artists, in an examination of themes such as colonization, identity, and institutional critique.

“My work is not made for Indian people but for thinking people. In the global and evolutionary scheme, the difference between humans is negligible.” –Carl Beam

Sources Cited:

“CV+Reviews.” Carl Beam, www.carlbeam.com/CV+Reviews.html.

Dion, Susan D., and Angela Salamanca. “InVISIBILITY:Indigenous in the city. Indigenous artists, Indigenous youth and the project of survivance.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 3, no. 1 (2014): 159-88. Accessed October 5, 2017. doi:10.1107/s0108768107031758/bs5044sup1.cif.