May 1 is the birthday of George Inness (1825-1894), an American painter who came of age in the era of the Hudson River School artists, many of whom strongly influenced his own work. Artists such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand inspired Inness in their approach to depicting landscapes and nature scenes. Seeing nature as a manifestation of the divine characterized much of the Hudson River School philosophy, but George Inness would take these ideas to an even loftier plane.

In celebration of George Inness’ 191st birthday, we excerpt selections from a 1990 catalog written by Crystal Bridges’ Director of Curatorial Affairs, Margi Conrads, wherein she discusses George Inness’ artistic training, his approach to landscape painting, and his impact on American art.

“The subject and process of George Inness’ art remained constant during his fifty-year career. Since the artist believed that reproducing man’s mark in nature was most worthy of expression, he chose to depict civilized landscape rather than the wilderness chosen by many of his peers. And instead of minute fidelity to the facts of nature, he focused on the emotions the landscape evoked through the use of indefinite forms and suggestive color.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (French, 1796 – 1875)

Italian Landscape (Site d’Italie, Soleil Levant), about 1835, Oil on canvas

63.5 × 101.3 cm (25 × 39 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles“The primary source of influence for Inness’ subject matter and aesthetic was French Barbizon painting, which he encountered during an 1853 trip to France. After the Civil War, the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875), and Theodore Rousseau (1812-1867) became very popular in the United States and was readily accessible to Inness in New York. Innes adopted especially Corot’s ordinary, unspectacular landscape views, rendered with a sense of intimacy through informal compositions, subtle coloration, and hazy atmospheric conditions. Avoiding the strictly factual, the Barbizon artists blended naturalism with lyricism to create images of nature at once real and poetic.

“As Inness matured, his Barbizon-inspired landscapes came to symbolize a higher power he saw reflected in the world around him through his growing commitment to the teachings of Swedish philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg. Fundamental to Swedenborgian ideas is the doctrine of correspondences. Alfred Trumble defined this central principle as:

God alone lives…. Our apparent life, our life on earth itself, is but the divine presence, which exists in individuals and in objects in different degrees.

“For Swedenborgians, the understanding of the correspondences between God and the physical world revealed the spiritual world, which in turn revealed the natural world in a new way.”

- American Paintings and Sculpture at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Margaret C. Conrads. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1990.

Crystal Bridges collection features two paintings by George Inness, on display in our Late Nineteenth -Century Gallery.

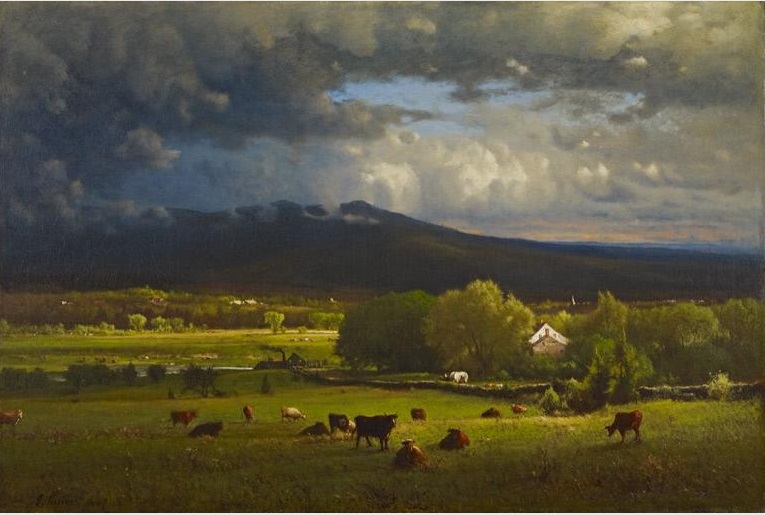

Sunset on the River, (above) a peaceful scene of cows grazing in a broad pasture with a church steeple crowned by looming, wrathful thunderclouds, suggests something of the renewed spirituality in Inness’s personal life and artistic practice as he adopted the spiritual philosophy of Swedenborg. While the storm clouds seem to threaten, they also unite the heavenly and earthly realms in the artist’s world, where natural cycles and seasonal rhythms signify constancy and the eternal. The canvas elicits emotional responses by way of dramatic lighting and deep vistas rendered with painterly brushstrokes.

George Inness (1825-1894), Sunset on the River, 1867. Oil on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photography by Steven Watson.

George Inness was an ardent abolitionist, yet his poor health prevented him from serving in the Union Army during the Civil War. The echoes of that great conflict resonated for Inness many years after the war’s end. An Old Roadway is one of a series of Inness landscapes from around 1880 in which figures play a prominent role. In these paintings, the artist addressed the aftermath of the Civil War while continuing to experiment with the atmospheric style for which he is best known. The subject of An Old Roadway—an African American woman with a walking stick and a pack over her shoulder interacting with a white boy tending sheep—likely relates to the migration of blacks from the South after the failure of Reconstruction. It also reminds viewers of slaves fleeing bondage before and during the conflict. In contrast to the modified picturesque compositions of Inness’s earlier work, such as Sunset on the River, this painting is divided into just two zones: the grassy foreground expanse and a visually impenetrable backdrop of trees. The lush foliage mingles with the green pasture, creating an almost unified field of color.

George Inness (1825-1894)

An Old Roadway, 1880

Oil on canvas

Photography by Dwight Primiano