July is the birthday month of two influential Modernists from the Crystal Bridges collection: Charles Sheeler (July 16, 1883 – May 7, 1965) and Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967). We’ll talk about Hopper a bit later in the week. Today we’ll focus on Charles Sheeler.

Sheeler was best known for his precise renderings of industrial and urban scenes emphasizing abstract, formal qualities. Sheeler was born in Philadelphia, where he studied at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Art (1900–1903) and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1903–1906) under William Merritt Chase (view his paintings in the Late Nineteenth-Century Gallery.) He made several trips to Europe between 1904 and 1910; the last one accompanied by his artist friend Morton Schamberg. After that, his works show influences of European Modernism and were characterized by clean lines, flatness, and reductive forms. He exhibited six of these Modernist works at the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York in 1913.

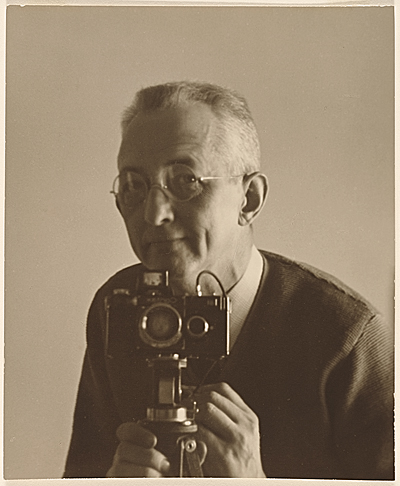

A talented photographer, Sheeler composed his paintings by arranging photographs and photographic negatives. Combining the heightened clarity of straight photography with his own interpretation of Cubism, he became the leading figure of Precisionism, a hard-edged realist style of the 1930s and ‘40s.

Crystal Bridges guests can experience a magnificent example of Sheeler’s Precisionist style in Amoskeag Mills #2 (1948, oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 24 in.), currently on view in the Early Twentieth-Century Gallery. The painting depicts a defunct manufacturing facility in New Hampshire that had been the largest cotton textile plant in the world at the turn of the twentieth century. Sheeler was inspired by the mill yard’s spare geometry, and painted the industrial scene in his signature pristine, hard-edged realism. The work also demonstrates Sheeler’s background as a photographer through the composition’s sharp focus and unconventional cropping that was typical in twentieth-century photography.

Sheeler took numerous photographs and made a tempera study of the site in preparation for painting Amoskeag Mills #2. Then he created a photomontage combining elements from several different photo negatives. Like the photomontage, the final oil version of Amoskeag Mills #2 presents a synthesis of multiple views. With the exception of the five-story Waumbec Mill at left, the buildings are a product of the artist’s imagination, composed of fragments of several other mill structures. They are sharply delineated by dramatic contrasts of prismatic light and shadow. Sheeler’s strangely sterile, uninhabited image reflects the decline of the New England textile industry beginning in the 1920s. Manchester’s Amoskeag Mills permanently closed in 1935, the victim of a combination of mismanagement, strikes, a flood, and the nation’s general economic downturn.[1]

Even though Sheeler’s paintings are characterized by a cold, Machine-Age aesthetic, he and other leading American Modernists, including Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Gaston Lachaise, were fascinated by folk art and became avid collectors of Americana. Especially Hartley, Demuth, and Sheeler shared an interest in developing a truly American art—a Modernism based on American themes and traditions. In 1959, Sheeler suffered a stroke and had to abandon painting and photography. His work is represented in many major American Museums. [1] Tamara K. Hareven and Randolph Langenbach, Amoskeag: Life and Work in an American Factory City (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 119, 293–359