Today is the birithday of artist Isamu Noguchi, born November 17, 1904.

In early 1929, Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) stepped into the splashy Romany Marie’s, a Greenwich Village tavern covered inside, floor to ceiling, by sparkling polished aluminum. The interior was designed by none other than Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), a regular customer who received payment for the design in the form of free meals from the proprietor.

Noguchi had just returned to New York from Paris after working for the sculptor Constantin Brancusi, who had some well-established connections to the bar he was walking into. Fuller was in the house that night, and received from the tavern owner an introduction to Noguchi that sparked an immediate friendship.

The immersive walls and ceilings—mirrored surfaces which cast no shadows—dazzled the younger Noguchi to the point that after months of regular returns for conversation, he produced a portrait bust in bronze depicting a chrome-plated Fuller buffed to a similar reflective finish. The two discussed a great many things and it was obvious they would each have a great influence on each other.

They collaborated frequently thereafter, each traveled the world in the course of their own work, yet never lost touch following that 1929 meeting.

Isamu Noguchi, Portrait of Buckminster Fuller, 1929, Chrome plated bronze, Noguchi Museum, Long Island City, NY

For decades, the pair constantly bounced ideas off each other, endlessly diving into science, math, nature, and spirituality. And, while it may not appear evident at first, I noticed some parallels between the monumental Fly’s Eye Dome and the ideas present in Noguchi’s tiny tripod, Gregory (Effigy), on view in Crystal Bridges’ 1940s to Now Gallery. Oblong and upright, metallic, Nogochi’s sculpture is diminutive in comparison to the 50-foot fiberglass half-orb, yet both works depend on basic, organic forms, a constant topic of conversation between the artists.

Isamu Noguchi, Gregory (Effigy), 1946 – cast 1964, bronze, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR

Noguchi took inspiration from the insect kingdom, designing his Gregory (Effigy) as a combination of fused biomorphic blobs, just as Fuller looked to the structures of a fly’s eye in desiging his final dome. Once I realized this, it became striking to link the tiny metallic beetle with the massive white dome. Both deployed an understanding of the natural world to different, but complementary ends: Noguchi to the universal humanity in all of us, and Fuller to universal human needs.

How refreshing is it to access understanding of an artwork through friendship?

These two were as unique from each other as their art, but both held an affinity for materiality, nature, and universal forms in their work. Most certainly, other artists explored organic motifs and deployed them in their work, but this backstory brings forward how the friendship of Noguchi and Fuller affected their work.

Both worked single-mindedly, and were fiercely independent as thinkers; so Noguchi probably didn’t have Fuller on his mind when he cast Gregory (Effigy). But in the context of their ongoing discussions about nature, structure, and form, the story becomes richer. For me, the conversation between Gregory (Effigy) and the Fly’s Eye Dome plays out also as conversation between Noguchi and Fuller.

Buckminster Fuller in front of the 50-ft Fly’s Eye Dome now installed on the Crystal Bridges north lawn.

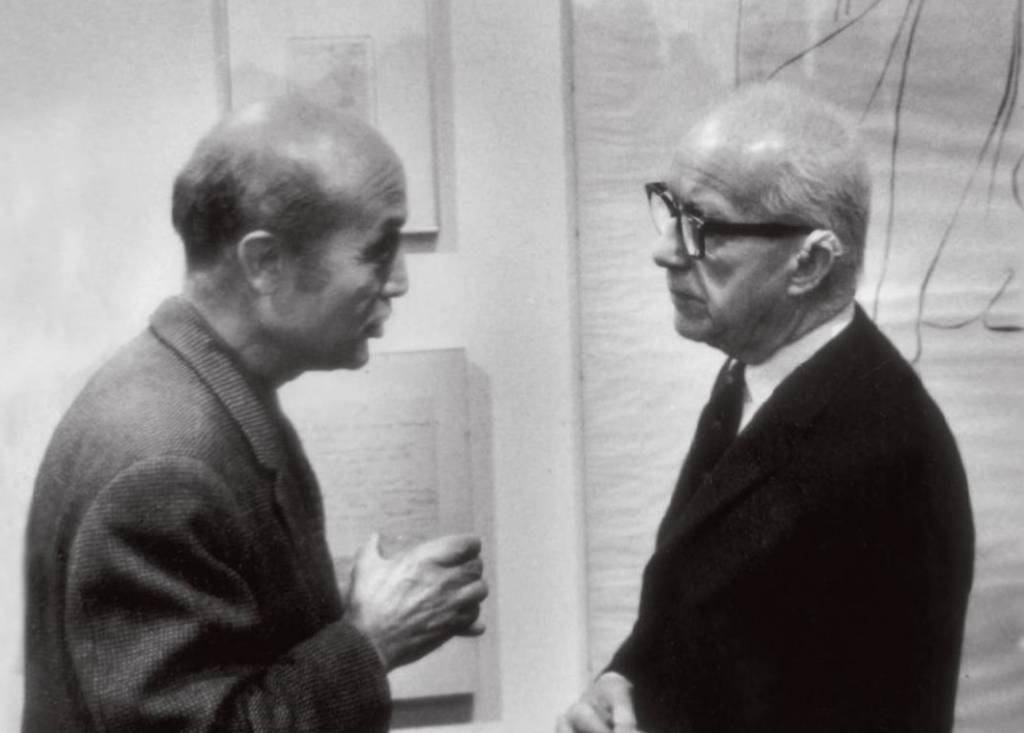

Photographer unknown, Buckminster, Anne, and Allegra Fuller with John Warren, Isamu Noguchi, and others, photograph, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR

Editor’s Note:

Also in Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection, Tom Sachs’s artwork Telegram, 2009 (not currently on view) takes the form of a Western Union telegram, crafted as a wooden triptych on a background of gold leaf. The telegram, from Buckminster Fuller, is addressed to Isamu Noguchi in Mexico City, and is signed “Bucky.” This is a faithful reproduction of an actual telegram that Fuller sent to Noguchi to explain Einstein’s theory of relativity in 1936 while Noguchi was working in Mexico on a public sculpture inspired by the theory. Having forgotten the specifics of the formula while he was there, Noguchi asked Fuller to fill him in. Fuller obliged, not only providing the equation E=Mc2, but also briefly explaining relativity and its significance in just 263 words.

Tom Sachs, b. 1966

Telegram, 2009

Gold leaf, pyrography, and synthetic polymer paint on plywood

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Sachs is not the only artist to be inspired by this remarkable telegram between these remarkable individuals. The Italian artist Elisabetta Benassi also recreated the telegram in hand-knotted wool carpet in 2009.

Elisabetta Benassi | Telegram from Buckminster Fuller to Isamu Noguchi Explaining Einstein’s Theory of Relativity |2009 | Hand-knotted wool carpet | 500 x 618 cm | Installation view Art Unlimited, Basel 2009

Transcript of copy:

WESTERN UNION

Isamu Noguchi Care Greenwood 66 Calle Republica Coumbia Mexico City

EINSTEINS FORMULA DETERMINATION INDIVIDUAL SPECIFICS RELATIVITY READS QUOTE ENERGY EQUALS MASS TIMES THE SPEED OF LIGHT SQUARED UNQUOTE SPEED OF LIGHT IDENTICAL SPEED ALL RADIATION COSMIC GAMMA X ULTRA VIOLET INFRA RED RAYS ETCETERA ONE HUNDRED EIGHTY SIX THOUSAND MILES PER SECOND WHICH SQUARED IS TOP OR PERFECT SPEED GIVING SCIENCE A FINITE VALUE FOR BASIC FACTOR IN MOTION UNIVERSE STOP

SPEED OF RADIANT ENERGY BEING DIRECTIONAL OUTWARD ALL DIRECTIONS EXPANDING WAVE SURFACE DIAMETRIC POLAR SPEED AWAY FROM SELF IS TWICE SPEED IN ONE DIRECTION AND SPEED OF VOLUME INCREASE IS SQUARE OF SPEED IN ONE DIRECTION APPROXIMATELY THIRTY FIVE BILLION VOLUMETRIC MILES PER SECOND STOP

FORMULA IS WRITTEN QUOTE LETTER E FOLLOWED BY EQUATION MARK FOLLOWED BY LETTER M FOLLOWED BY LETTER C FOLLOWED CLOSELY BY ELEVATED SMALL FIGURE TWO SYMBOL OF SQUARING UNQUOTE ONLY VARIABLE IN FORMULA IS SPECIFIC MASS SPEED IS A UNIT OF RATE WHICH IS AN INTEGRATED RATIO OF BOTH TIME AND SPACE AND NO GREATER RATE OF SPEED THAN THAT PROVIDED BY ITS CAUSE WHICH IS PURE ENERGY LATENT OR RADIANT IS ATTAINABLE STOP

THE FORMULA THEREFORE PROVIDES A UNIT AND A RATE OF PERFECTION TO WHICH THE RELATIVE IMPERFECTION OF INEFFICIENCY OF ENERGY RELEASE IN RADIANT OR CONFINED DIRECTION OF ALL TEMPORAL SPACE PHENOMENA MAY BE COMPARED BY ACTUAL CALCULATION STOP

SIGNIFICANCE STOP

SPECIFIC QUALITY OF ANIMATES IS CONTROL WILLFUL OR OTHERWISE OF RATE AND DIRECTION ENERGY RELEASE AND APPLICATION NOT ONLY OF SELF MECHANISM BUT OF FROM SELF MACHINE DIVIDED MECHANISMS AND RELATIVITY OF ALL ANIMATES AND INANIMATES IS POTENTIAL OF ESTABLISHMENT THROUGH EINSTEIN FORMULA

BUCKY

Sources:

Sadao, Shoji. Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi: Best of Friends. Milan: 5Continents, 2011.

Wolf, Amy. On Becoming an Artist: Isamu Noguchi and His Contemporaries, 1922-1960. Long Island City: The Noguchi Museum, 2010.