Mexico and the United States have a long paradoxical history together, characterized by territorial exchange and war, but also cooperation and peace. Following the theme of Border Cantos, the Crystal Bridges Library will explore American travels through the country of Mexico during the nineteenth century and the often tense relationship between the United States and Mexico that culminated in the Mexican-American War.

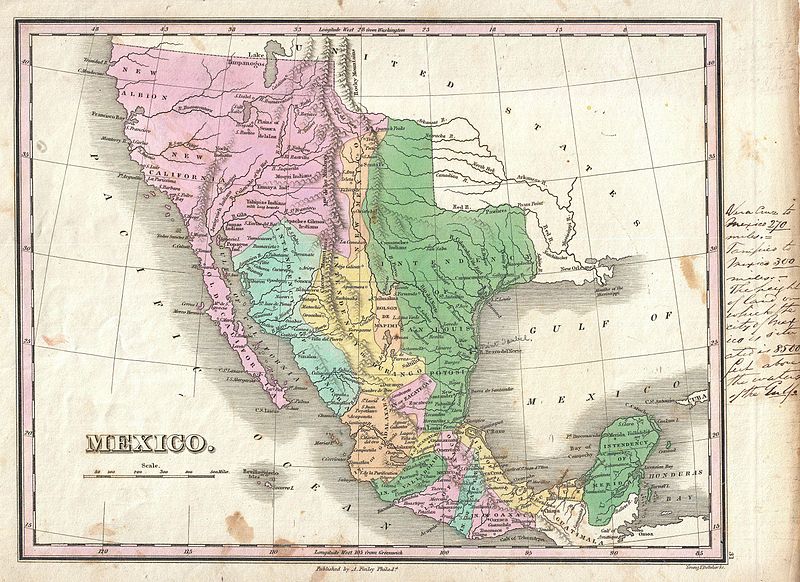

Border disputes were common for Mexico and America in the nineteenth century. At one time, Mexico controlled the modern-day states of Arizona, Texas, California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. During the 1840s, as many American settlers were making their way into Mexican territories such as California and Texas, the United States sent governmental diplomats and consuls to the region to gain a better understanding of these areas.

From Travels over the Table Lands and Cordilleras of Mexico during the Years of 1843 and 1844 by Albert Gilliam in 1846,

“But the most celebrated of all, and probably the most superior on the American continent, is the harbor of San Francisco, situated upon the beautiful and capacious bay of that name. This harbor gives to California, with its fine climate and productive soil, great and incalculable advantages over any other country of the western coast, because it presents commercial facilities of so commanding a character, as to render it, in the hands of an enterprising people, the great depot of the Pacific.” (p. 386)

American interest in the territories of Mexico, especially Texas, prompted many writers to suggest that it was not only beneficial for America to have these territories in its possession, but also that America should annex these regions because it was the morally correct thing to do. John Frost, a teacher turned popular writer, was a well-known embellisher of American history, as he believed American nationalism should be at the core of historic understanding. When Texas fought Mexico for its independence in 1835-36, Frost painted the conflict in very different colors: claiming that the territory’s hard-won battle for freedom from Mexico was in fact a strategic move by the Republic of Texas to become part of the United States.

From Frost’s Pictorial History of Mexico & the Mexican War by John Frost in 1848,

“Texas began to feel herself inadequate to the harassing struggle, which rendered formidable even the weakness of her obstinate foe. Her only resource was the establishment of such a relation with the United States as would awe Mexico, and secure to herself safety and respectability, both at home and abroad. She had apparently battled, not so much for absolute independence, as for emancipation from Mexican tyranny; and in order to secure this object, she laid less stress on national sovereignty, than upon a state of dependence which would insure her safety.” (p. 178)

US troops marching on Monterrey in northern Mexico during the Mexican-American War in 1851

Tensions between Mexico and the United States continued to grow as more and more Americans made their homes in Texas, California, and the other Mexican territories. A powerful belief in Manifest Destiny and a desire to resist the British attempts of colonization beyond the Oregon territory in the West fueled American expansionism. The Mexican government viewed American encroachment in their territories as aggression, while skirmishes between Mexican and American settlers were seen as the final straw. As Mexico and America prepared for war, reports from the American military to the government were crucial in setting out a strategy for the war with Mexico.

From Hughes Report, Report of the Secretary of War in 1849,

“The country to be traversed presented difficulties of no ordinary nature to an invading army, being for long distances destitute of water and subsistence–in fact, mere desert wastes. In both cases the communications must have been abandoned, thus violating one of the first principles of war, unless forced by a stern necessity.”(p. 32)

Native Americans also proved to be a problem for Mexicans and Americans alike. Tribes like the Apache and Comanche were especially difficult to defeat in the northern Mexican territories, much of which was only sparsely settled. Americans attempting to map the region noted many of the peoples they encountered.

From Reports of the Secretary of War, with Reconnaissances of Routes from San Antonio to El Paso

“The proposed camp at the mouth of the Little Wichita should hold in check the fierce bands of northern Comanches- the destroyers of Bent’s fort, the pest of the western routes, and the fiercest and most intractable plunderers of Mexico known. To the western pass those large bands of Comanches, which, secure in the recesses of the Sierra Madre and the Bolson de Madpimi, carry on such extensive forays in the Mexican States, returning with incredible numbers of horses and mules.” (p. 24)

You can see the books quoted in this post on display in the Crystal Bridges Library for the duration of the temporary exhibition Border Cantos: Sight & Sound Explorations from the Mexican-American Border. Additional information related to Border Cantos can be found in the Library on the endcaps as highlighted books.