What is Blackwell’s Island?

An oil painting by Edward Hopper? Yes, but where and what is the actual Blackwell’s Island? Why did Hopper choose to paint it? These are questions that I asked myself recently while preparing for the installation of the new temporary exhibition, Edward Hopper: Journey to Blackwell’s Island. Looking at the image, I wanted to know more about the place that I was seeing. It seemed so mysterious to me. I decided to start digging, and what I found was a surprising and complex history.

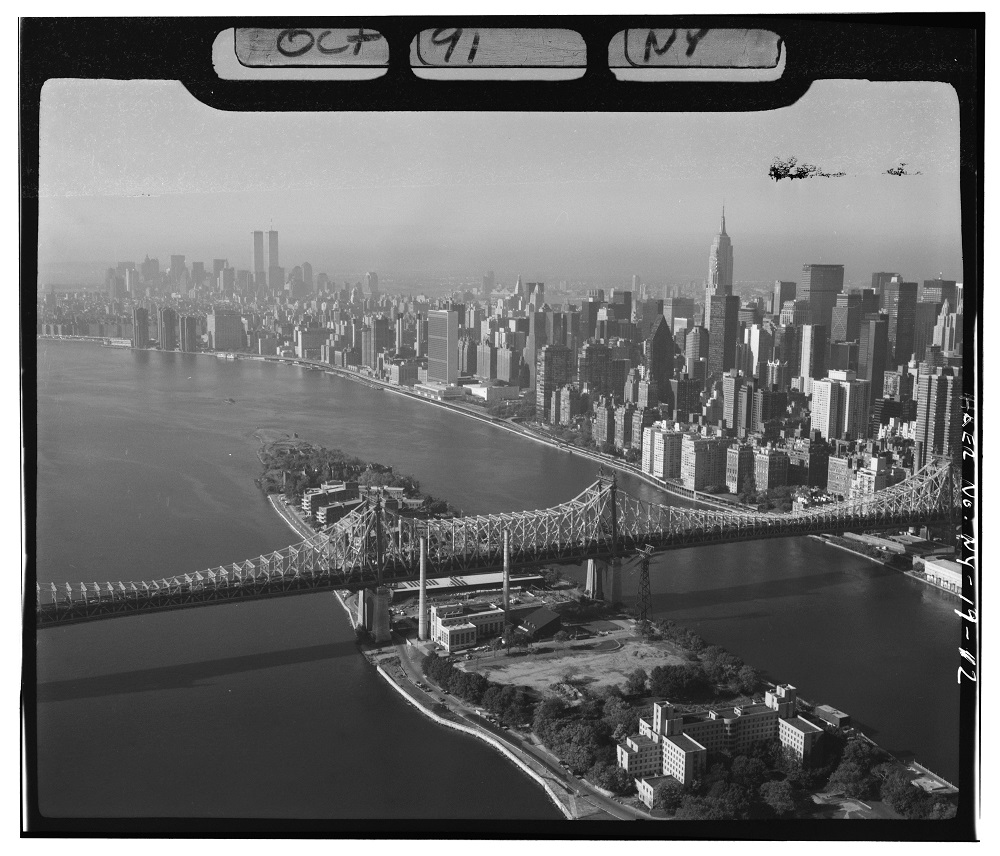

Blackwell’s Island, known today as Roosevelt Island, is a tiny sliver of an island in New York’s East River between Manhattan and the borough of Queens. The island has had several names over the centuries and multiple owners. The first residents of the island, then known as Minnahanock, were the Canarsie Indians. In1637, the Indians sold the island to Governor Wouter van Twiller, an employee of the Dutch West India Company. During this time the island was used as farmland and known by the Dutch name Varckens Eylandt or Hog Island (the Dutch raised hogs there). In the late 1700s, it was owned by the Blackwell family, hence the name Blackwell’s Island. Two brothers, James and Jacob Blackwell, were the last of the family to own the island. Their financial problems forced them to put the island up for sale, and it was sold to the City of New York in 1828. The city decided to use the island as a secluded and peaceful location to construct institutions that focused on both physical and mental rehabilitation. This included a penitentiary, lunatic asylum, almshouse, workhouse, and charity hospitals.

Over the next century, there were many changes and additions to the institutions on the island, but the island’s purpose remained the same. In 1921, the island was renamed Welfare Island, a name that reflected its main use. Throughout the twentieth century, many of the buildings fell into disrepair and some were demolished. Luckily, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, established in 1965, was able to step in and preserve some of the structures. In 1973, the island was renamed Franklin D. Roosevelt Island in honor of the 32nd President of the United States. The island soon became home to over 2,000 new apartments, and Roosevelt Island today serves a mostly residential purpose. Only six original structures remain:

-

Blackwell House – Blackwell House is the only standing structure that was part of the island when it was still privately owned. The eighteenth-century clapboard farmhouse was built for James Blackwell. Throughout the nineteenth century, the house was used by administrators of the island’s various institutions, including the warden of the almshouse. By the 1960s the house was in poor condition. A complete restoration by architect Giorgio Cavaglieri in 1973 returned the house to its former glory.

-

The Octagon, after the hospital wings were demolished, but before the new residential wings were built.

The Octagon – The Octagon is the only remaining part of what was once the New York City Lunatic Asylum. The asylum was designed by architect Alexander Jackson Davis and built in 1839. It was one of the first institutions of its kind. After struggling with poor staffing, overcrowding, financial hardships, and disease outbreaks in the mid-1800s, facility upgrades were made that greatly improved the conditions of the asylum. In 1894, the asylum patients were moved to a new facility on Ward’s Island. The Octagon building then became Metropolitan Hospital, the predominant building that you see in Edward Hopper’s Blackwell’s Island. When the Metropolitan Hospital moved to Manhattan in the 1950s, the building lay vacant. Its two wings were demolished in the 1970s, leaving only the central octagon-shaped structure. The Octagon is fully restored today, and two new wings of apartments have taken the place of the old hospital wings.

- The Smallpox Hospital –This hospital, designed by architect James Renwick, was built for the treatment of smallpox in the 1850s. In 1875, it became a nursing school. By the 1950s the building was abandoned, and it stands as a preserved ruin today.

-

The Lighthouse – Located on the northern tip of the island, the lighthouse warns of the river’s treacherous current. It was designed by architect James Renwick, who also designed the Smallpox Hospital, and built in 1876. It stands at 53 feet tall.

- Chapel of the Good Shepherd – This Victorian Gothic Chapel was designed by architect Frederick Clarke Withers. Construction started in 1888 and was completed in 1889. The chapel was used by the inmates of the island’s almshouse. After closing in 1958, it was restored by architect Giorgio Cavaglieri and reopened in 1975. Today, it serves as both a community center for island residents and a place of worship.

- The Strecker Memorial Laboratory – Designed by architects Frederick Clarke Withers & Walter Dickson, the laboratory was built in 1892. It was used for the study of disease. The building contained a specimen exam room, an autopsy room, and a mortuary. Later, in 1905, a third floor containing a histological facility and a library was added. After being unused for some time, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority converted it into a power conversion substation for the island’s underground trains.

After discovering the history of Blackwell’s Island, it became obvious to my why an artist like Edward Hopper would want to paint it. Like many of his other subjects, the island is set apart and secluded, not just in its location but in its purpose. For me, its history as a retreat for the troubled, the unfortunate, and the ill gives the island a certain charisma, a magnetic mystery. Hopper captured this feeling is his painting of Blackwell’s Island, and I think that is why the island captured me.

Please don’t miss Edward Hopper: Journey to Blackwell’s Island which will be on view January 18 through April 21. The exhibition includes preliminary sketches on loan from the Whitney Museum of American Art, the finished painting and other watercolors from the Crystal Bridges permanent collection. Also, if you are interested in learning even more about Roosevelt Island, please visit the Roosevelt Island Historical Society website.