Kara Walker, b. 1968

“A Warm Summer Evening in 1863” 2008

Wool tapestry and felt

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR

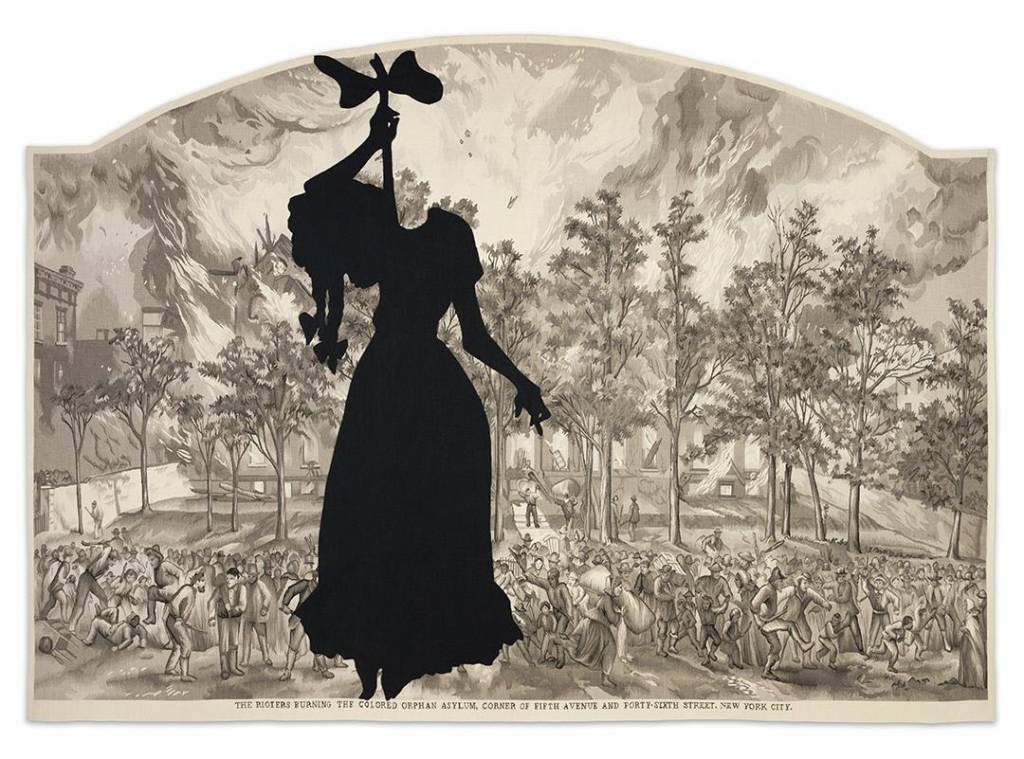

Looming large against a chaotic illustrated scene, the caricatured silhouette of a hanged young black woman sets a dark tone for Kara Walker’s tapestry, A Warm Summer Night in 1863. Set in the past, this work offers a layer of removal from the present day. By focusing on a historical scene, Walker creates breathing room to reflect on the now. In all of her work, she frames the continued repercussions of racism throughout US history as a starting point for discussing racial injustice among today’s audiences. This approach allows viewers to engage with a politically charged topic in the abstract. The past becomes a safeguard for reflection upon the present.

Kara Walker

Particularly in this work, there is an added layer of political drama. The image comprising the background originally appeared in the newspaper Harper’s Weekly, August 1, 1863, and reads, “The rioters burning the colored orphan asylum, corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty-Sixth Street, New York City.” Leading up to Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, many white, working-class Americans in the North feared that freeing the enslaved would result in added competition for jobs due to an influx of black workers fleeing to northern states. This fear, coupled with an expanded draft law that targeted a broader swath of white men, resulted in riots in the streets of New York City on July 13. While innocent New Yorkers of every cultural and racial background were subjected to violence during this protest, Harper’s Weekly, and later Kara Walker, seized upon one atrocity in particular: the burning of this orphanage.

This event represents an attack upon some of the most vulnerable victims imaginable. And understandably, for a pro-abolitionist paper like Harper’s Weekly, it was a powerful scene that helped to prompt a deeply emotional connection to the riots for Americans of all cultural backgrounds– one which was further emphasized by the paper’s decision not to mention that all of the orphans were whisked away to safety. And yet despite the publication’s good intentions, in the original imagery and in the accompanying newspaper article, the emphasis is less on the victims and more on the rioters themselves and the bravery of a white fire chief and others who tried to counter the attacks. Nevertheless, the passage of more than a century-and-a-half has done little to diminish the emotional impact of this scene, and Walker’s additions help to redirect the viewers’ focus back onto the innocent orphans.

Illustration from Harper’s Weekly, August 1, 1863

Created in 2008, Walker’s tapestry predates the high-profile deaths of young African Americans like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Even before these tragedies and the groundswell of activism that followed, her work speaks to a continued culture of racial injustice in this country. Today, given the proliferation of coverage splashed across the news and social media, Walker’s artwork, which itself draws directly on an earlier form of mass media, embodies a timely reminder of a continued tradition of brutality playing out on the streets and disseminated in the media sources of each successive generation.

Walker pulls back the veil. The media, whether a weekly newspaper from the 1800s or a web-based video making the rounds on social networks, always reveals a certain bias. A free and open press is fundamental to the success of our country and should never be censored or silenced. But it is incumbent upon our citizens to also realize that no story is completely without inflection from its source, and Walker’s point is that historically, this often comes at the expense of the black community. By employing the silhouette motif in this work, Walker re-centers the attention onto the victims, and encourages all of us to bring an equally probing eye to our consumption of media today. —AB

–A version of this article was previously published in C magazine, Crystal Bridges’ publication for museum Members.

Lynching in African American History

During the New York Draft Riots, as many as 500 people lost their lives, though some estimates go much higher. Several police officers were killed, and the homes and businesses of many of the city’s wealthy whites were burned or looted. Although they had nothing to do with the levying of the draft, the city’s Black population were the target of the mob’s most violent outrage. Any Black individual—man, woman, or child—unfortunate enough to encounter the rioters, was set upon, beaten, and perhaps lynched, mutilated, and burned.

Although lynching occurred more frequently in the South, in truth African American men and women were lynched in communities large and small across the United States—According to the Equal Justice Initiative’s 2015 report, Lynching in America, more than 4,000 Black people were lynched between 1877 and 1950. A group called Monroe Work Today has created an interactive map that notes every lynching they have able to document between the 1830s and 1960s: a shocking visual record. Even more shocking, many of these events were planned affairs, which crowds of white folks of all ages turned out for to watch and photograph. In the early twentieth-century, a brisk business developed in the printing and distribution of picture postcards documenting lynchings.

This history is disturbing, but it is important that it not be lost or forgotten. Art is vital in bringing difficult subjects to the fore so that they can be contemplated, discussed, and remembered in a safe environment and within historical and social context. Often art speaks to us on an individual level that is more deeply moving than any news report. Art is humanizing, and affects us in so personal a way that it can help to remind us of our shared humanity, remove barriers, and build bridges.

Paul Rucker

The history of lynchings in America will be the subject of an upcoming Performance Lab program at the Museum on March 30. Artist, composer, and musician Paul Rucker will perform his cello compositions to accompany Stories from the Trees, a series of video animations based on images in historical lynching postcards.

Rucker’s performance at Crystal Bridges will kick off Northwest Arkansas’ INVERSE Performance Art Festival, scheduled for March 30 through April 1, 2017.