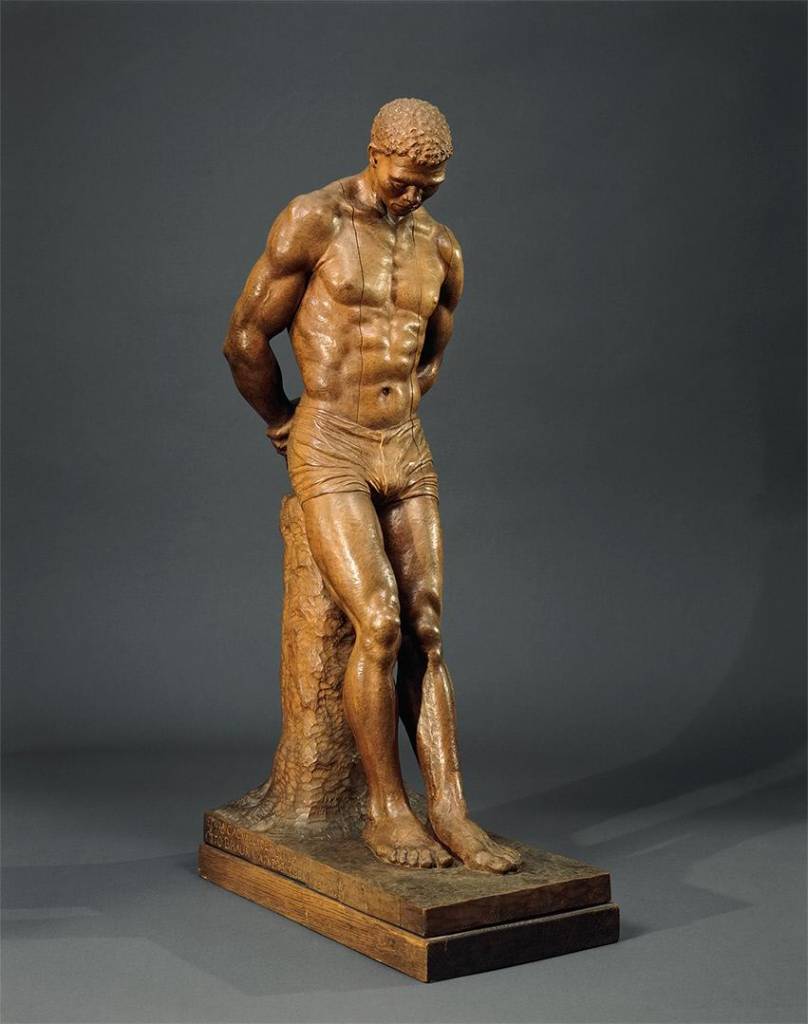

after Emma Marie Cadwalader-Guild (1843 – 1911)

“Free”

Modeled 1876, carved after 1876

Basswood

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonviille, Arkansas

One of the works in Crystal Bridges’ collection that speaks most movingly about the experience of African Americans during the Restoration period was actually created by a White woman. Today’s blog post on Emma Cadwalader Guild’s sculpture, Free, comes to you from Museum Educator Raven Cook and Protection Specialist Kentrell Curry.

The story of Emma Cadwalader Guild’s sculpture Free begins fairly early in the artist’s career, when Cadwalader-Guild was enjoying the company of a friend in Boston and spotted a Black man who was seemingly in trouble. His posture, reflecting a discontented circumstance, led Guild to immediately be drawn to him as a subject for her artwork. The story was later retold in a 1904 issue of Pearson’s Magazine:

And without ever having had a lesson in clay, she engaged the man then and there to become her subject. For weeks she toiled and worked unceasingly before this model. She struggled with the plastic clay as though its touch inspired her; she never wearied until she had molded it into the vision that she saw within her own soul. She had the statue cast in Italy. She called it “Free.”

Cadwalader-Guild−a white, female, self-taught sculptor−utilized her artistic skill to depict in tangible artistry the complexities of the Black experience. Little is known as to why Cadwalader-Guild felt such a strong connection to the subject, but she was likely making a statement about the continued mistreatment of African Americans by the government, even after the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and Reconstruction Amendments (1865 and 1870), which afforded them—nominally, at least—equal rights.

The work in Crystal Bridges’ collection is a copy of Cadwalader-Guild’s original bronze sculpture, which has been, unfortunately, lost to history. This version was carved in basswood around 1911 by a German artist, Otto Braun. Cadwalader-Guild spent most of her adult life in Europe, mostly in Germany.

Free depicts a Black man with his head bent downward and his arms behind his back. The viewer might immediately assume the subject is in bondage, but as they make their way around the piece, they will notice that the figure is not bound by physical restraints. The question then becomes: Can freedom be denied in other ways? If so, what are the psychological effects on the oppressed?

In the twentieth century, Jamaican leader Marcus Garvey said, “Liberate the minds of men and you will liberate the bodies of men.” Perhaps viewers consider the title of Free and recognize that freedom must not just take place on the bodies of the oppressed but in the minds.

Citations

Gupta, Sanjay. “Balancing and Checking.” Essays on Modern Democracy. Ed. Bob Towsky. Hinsdale: Brook Stone Publishers, 1996.

Gerdts, William. “Emma Cadwalader-Guild.” Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art object files, 2016.

Abbie G. Baker, “An American Woman Sculptor.” Pearson’s Magazine, 11, 1904, p. 171.