Imagine the difficulty of supporting yourself as a biracial artist in the United States prior to the Civil War. Robert Seldon Duncanson did just this—establishing an artistic practice in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1854, first as a photographer and then as a full-time painter. At the time, Cincinnati was an economic and cultural center and Duncanson found many patrons for his work. By 1861, a Cincinnati newspaper claimed that Duncanson was “the best landscape painter in the West.”

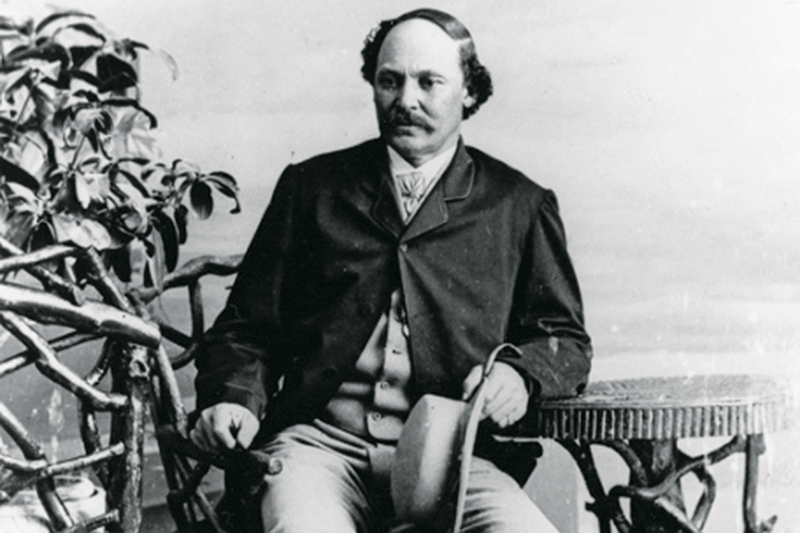

Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821 – 1872)

Landscape, 1865

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Duncanson was born to a Scottish-Canadian father and an African American mother in 1821 in Seneca County, New York. By the early 1840s he had settled near Cincinnati with his mother. Duncanson initially taught himself fine art by copying prints and working as an itinerant portrait painter between Cincinnati and Detroit. In 1853, Duncanson embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe, through England, France, Italy, and possibly Germany, to study the European masters. By the time he returned from Europe, landscape had become his predominant subject, painted in the style of the Hudson River School—a group of mid-nineteenth-century artists named for their origins in landscape scenes near the Hudson River. These artists, like Duncanson, combined details of nature based on close observation with idealized elements to emphasize the beauty and grandeur of the wilderness.

Duncanson spent much of the Civil War in Minnesota, as well as Toronto and Montreal, Canada, far from the hostilities and the racial tensions present in Cincinnati, near the border of North and South. When Duncanson arrived in Montreal he was warmly received, and he exhibited his works there to great acclaim. In Landscape, painted while in Canada, Duncanson depicted loggers floating rafts of timber down what is most likely the Saint Lawrence River, near Montreal. Despite the intimate scale of the painting, the view highlights the broad expanse of the river valley. The entire composition is bathed in the golden glow of sunset, a visual effect that unifies the scene and recasts a mundane, workaday activity.

In 1865, Duncanson left Canada to visit the British Isles, returning to America and Cincinnati by 1866, after the close of the Civil War. Despite racial discrimination and oppression, Duncanson nevertheless was highly regarded as an artist and continued to be successful throughout his life. Tragically, he suffered a form of dementia toward the end of his life, possibly due to poisoning from lead-based paint, and died suddenly in 1872 while working on an exhibition in Detroit.

Note: Duncanson’s work is off-view at Crystal Bridges while the museum’s Early American Art Galleries are undergoing redesign. This work and others from our historical collection will be back on view when the gallery reopens in mid-March. In the meantime, be sure to visit our exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, on view through April 23.